Sfurti micronutrient sachets: The journey so far and challenges ahead

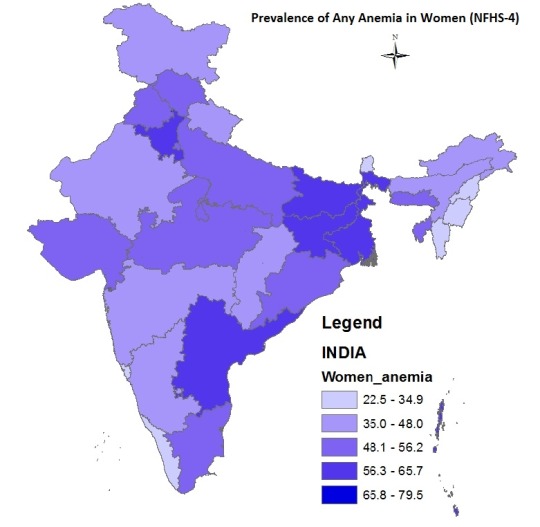

Iron, an important micronutrient for normal body functioning and stamina, is deficient across the world and severely affects women and children in developing countries as reported by WHO. Common symptoms of iron deficiency lead to lower level of stamina, fatigue and muscle pain, consequently decreasing productivity and hence, the standard of life. Despite such serious consequences, dietary iron intake is low in several parts of India, often due to ignorance and lack of awareness.

Songadh block in Tapi district in the state of Gujarat is one such area. Most of the population is iron deficient with some even suffering from sickle-cell anemia, a disease worsened when coupled with iron deficiency.

Last June (2016), the Tata-Cornell Institute (TCI), in collaboration with our partner agencies, introduced a home-fortificant in 15 target villages in Songadh block. Branded under the label ‘Sfurti’ – meaning healthy – this powder, in addition to iron, provides for other critical micronutrients such as folic acid and vitamins A and B12. It is marketed in small sachets reasonably priced at Rs. 3, and if mixed with 5 kg flour (wheat or rice), it satisfies the micronutrient needs of the household. Owing to the lack of awareness around the importance of micronutrients, a door-to-door mobile vendor marketing model was employed to sell Sfurti, as well as create awareness about iron and other micronutrients, through trained women self-help group members called ‘Sfurti Bens’ (Sfurti Women).

Lessons Learned

Phase-1 of the project concluded on the 31st March, 2017. Over the course of about 9 months, 5,500 households over 15 villages were reached. What factors contributed to the intervention’s positive beginnings?

Here are a few key takeaways:

- The coverage (defined as at least one time buyers) grew over the period (albeit slowly) reaching ~66% at the end.

- Grassroot level marketing efforts raised awareness and facilitated take up.

- In the absence of local government assistance, dairy cooperatives and women self-help groups (SHGs) were important allies for outreach efforts.

- ASHA workers (female community health workers) helped to build confidence in the efficacy of Sfurti.

Outreach session in target village. (Photo credit: Jessica Ames)

Unintended Consequences

However, feedback from across the villages about Sfurti was widely varied – from people completely dismissing Sfurti to people over-enthusiastically, and also incorrectly, trusting Sfurti to be a solution for most of their health problems. A few consumers in informal interviews reported implausible cosmetic changes such as softening or whitening of their skin (in this region, fairer skin is considered a beauty ideal, and hence an aspiration), reduction in hair fall, etc. Even in cases where the claims were legitimate – such as increase in appetite or reduction in fatigue or joint pains – often the claimed extent of improvement seemed dubious. This was further corroborated by discussions with the doctors at the Primary Health Centers who felt that the reported effects could be a placebo effect, if not misreporting.

Another unintended yet interesting effect was the increased sense of empowerment among the Sfurti Bens. Door-to-door marketing for Sfurti gave these women an opportunity to engage with other villagers, especially women, and consequently earn a politically elevated status within the village. Some of these women even went on to win the Gram Panchayat (local village level) elections. This is a particularly interesting fact in the assessment of Sfurti. Since door-to-door sales are driven more by the pitch than the product and a sense of respect being attached to the Sfurti Bens, a strong underlying factor for increased sales could be peer pressure. This connects back to why households reported exaggerated and implausible effects. Although there isn’t strong evidence, nevertheless it is possible that people are not actually consuming the powder, despite buying it.

Field coordinators training Sfurti Bens. (Photo credit: Jessica Ames)

Conclusions

Going forward, it is important to understand why people choose to buy Sfurti (and continue to buy or opt out) and the many factors which may influence decision making. If peer effect is a strong driver, then it is imperative to go a step further and validate that they buy and consume it. In the end, it is only beneficial if through the consumption of Sfurti, people realize the value of micronutrients through an (actual) improvement in their health. It is a rather complex research question to crack, but an interesting one.

Plans are afoot to conduct household level interviews of a random sample of these villages. Food samples from the households can help distinguish between actual consumers and mere buyers. This coupled with trends in sales, interviews with Sfurti Bens and information on the marketing efforts made during the period can help empirically tease out answers to most of these questions.

Given, food consumption in most rural areas is through the informal market, being able to answer what drives people to voluntarily invest in consumption can help improve the status of nutrition in these, often left behind, regions.

By Prankur Gupta

Prankur Gupta is a Master’s of Science student in Applied Economics and Management at Cornell University’s Charles H. Dyson School of Applied Economics in Management. His research with the Tata-Cornell Institute (TCI) focuses on consumer behaviors in rural Gujarat.