Are India’s Farmers Taking Advantage of Web-based Technology?

In this blog post, TCI scholar Vanisha Sharma investigates how farmers in India’s impoverished rural areas are using the internet to boost agricultural productivity.

Beginning in 2016, a public-private partnership called Jio laid 250,000 km of fiber optic cable throughout India. It was the start of India’s “internet revolution,” which brought with it extremely low prices, especially for mobile data. Jio’s 4G internet service costs a mere $2 per month for unlimited use, and by 2019, it reached 331 million customers in both rural and urban areas.

Long before the advent of the internet, agriculture technology has played an important role in boosting agricultural productivity. Mechanized labor like tractors helped make farmer workers more efficient, and plant-breeding technology produced more nutritious and resilient crops. As an information communication technology, the internet plays an important role in disseminating agriculture-related information, such as weather estimations and training for best practices.

As low-cost service increased internet access in India’s impoverished rural areas, I wanted to know how research institutes and development organizations are incorporating it into their agricultural interventions, and how farmers are taking advantage. So, with the support of the Tata-Cornell Institute, I traveled to India to conduct interviews with farmers and experts in the field.

Current Frontier

The digital agriculture team at the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT) is working towards increasing farmers’ usage of apps that can help with agriculture.

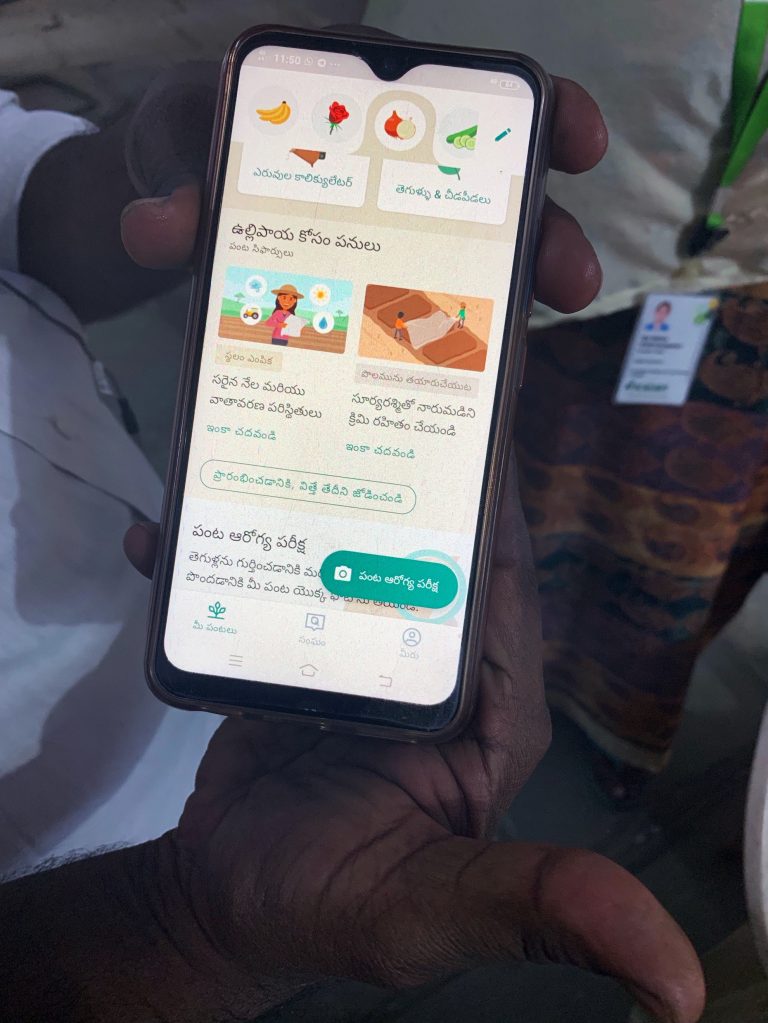

On such app is Plantix, a classic example of how artificial intelligence and machine learning can be integrated into agriculture. Developed in Berlin, the free app uses deep-learning techniques and neural networks to diagnose plant diseases, pest damage, and nutrient deficiencies, and offer corresponding treatment measures. Farmers simply use a smartphone to take a picture of their sick or damaged crops and receive a diagnosis and solution through Plantix. In case of poor connectivity, the app has an offline library of plant diseases. In India, the app has been launched in more than eight local languages and has been used by around 100,000 farmers in the states of Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, and Telangana.

“If I carry a smartphone onto a paddy field and it falls in the water, then the cost of repairing the phone is more than buying the phone itself,” one farmer said.

However, for a variety of reasons both social and economic, farmers are not always quick to adopt technology. As ICRISAT’s digital agriculture team pointed out, farmers have trade deals with traders they have known for a long time, and digitizing this process may cost them the feeling of security that comes with human connection.

More research needs to be conducted regarding optimizing the use of technology in agriculture.

Infrastructure Challenges

In the villages of Ismailkhanpet and Kulabgur in Telangana, most farmers owned a regular phone handset unable to run web-based applications like Plantix. There were many reasons farmers were unwilling to invest in smartphones. “If I carry a smartphone onto a paddy field and it falls in the water, then the cost of repairing the phone is more than buying the phone itself,” one farmer said. “So, we choose not to buy a smartphone at all.” To see how farmers interacted with internet-based technology in practice, I met with around 50 farmers across seven villages in the southern states of Telangana and Andhra Pradesh. The interviews revealed granular differences in each community, with varied behaviors across social circles.

Other farmers brought up literacy issues and were resistant to using new technology. “If we really need to look something up the internet, we ask our children to help us,” said a middle-aged farmer.

A farmer distinguishes between a pest-infected and healthy chili crop. (Photo by Vanisha Sharma)

Mulkanoor is a special locality because it is the epicenter of a rural cooperative bank that facilitates credit markets, seed distribution, and agriculture extension services to villages within a 25-km radius. In a location with a well-functioning, tangible infrastructure in place, farmers seemed less inclined to use apps for digital agriculture. “If I need help with pesticides, I simply make a call to the bank and they send an officer for help,” one farmer said.Some indicated initial interest in the app when officers from ICRISAT, in collaboration with Plantix, visited the villages to demonstrate the application, but later uninstalled the app because they did not find it too useful. “If I do need any information, I just use Google or YouTube and don’t need apps,” said a farmer in Mulkanoor, a village three hours north of Hyderabad.

When asked if they would prefer an instantaneous response to their query—it takes about a day to receive help from an extension officer, compared to 10-15 seconds on Plantix—they said that they would prefer to receive advice in person, as opposed to an app. This indicates that it may be more difficult to build trust in virtual, as opposed to physical, infrastructure.

In contrast, most farmers in Andhra Pradesh, especially in the villages neighboring the town of Nandyal, owned smartphones and had either heard of or were using Plantix.

Nandyal is where the Regional Agricultural Research Station is located. ICRISAT scientists routinely send high-yielding variety seeds with new technology to some farmers in nearby villages for trial. If the yield looks promising, the rest of the farmers continue to adopt the new variety.

As in Mulkanoor, geographic proximity to a well-functioning support system has resulted in a trusting relationship between the farmers and the Research Station. Yet, in Nandyal farmers welcomed internet technology, whereas Mulkanoor’s farmers avoided it. Why would this be? However, despite RARS, the farmers in Andhra Pradesh (as opposed to in Mulkanoor, Telangana), were more optimistic about using digital agriculture.

Internet-assisted, digital agriculture has immense potential to benefit farmers in rural communities, but first they must decide to use it. My preliminary research in southern India indicates that contextual differences drive the demand, or lack thereof, for digital agriculture. Additional research is needed in order to gain a better understanding of how social networks influence farmers’ decisions to adopt new technology.

Vanisha Sharma is a second-year PhD student in the Dyson School of Applied Economics and Management at Cornell. Her research interests lie in the intersection of agriculture, malnutrition, and networks and digitization in rural communities.