Bringing Intelligence to the Fields: Opportunities and Equity in India’s AI-driven Agriculture

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is no longer confined to labs and tech hubs. Today, it is transforming agriculture—tailoring weather advice for farmers and spotting pests before they decimate crops. As IBM defines it, AI is “technology that enables computers and machines to simulate human learning, comprehension, problem-solving, decision-making, creativity and autonomy.” In India, home to over 150 million farmers and one of the world’s largest agricultural economies, AI holds immense potential to improve livelihoods, reduce climate vulnerability and make food systems more resilient. Yet, as the country surges ahead with ambitious AI initiatives, crucial questions about equity, sustainability and inclusion remain.

The global rise of AI in agriculture

Around the world, AI is helping farmers optimize crop planning, reduce input usage and forecast yields. Tools like Trapview capture pests in a field and use computer vision to identify them. Once identified, the application collates information about geographical and weather information and sends farmers a report on the impact and possible extent of damage from the pest. In the U.S., John Deere’s AI-enabled precision farming equipment, “Autonomous,” adjusts seeding and tillage in real-time.

In India, too, AI is becoming deeply embedded in the agrifood ecosystem. Take AquaConnect, a Tamil Nadu-based platform using AI and remote sensing to create a more transparent and efficient aquaculture value chain. Or DeHaat, which aims to provide end-to-end solutions and services to India’s farming community. Intello Labs, another home-grown success, uses AI-powered image recognition to grade agricultural produce, reducing waste and inefficiency across the supply chain.

Government-supported initiatives also show promise. Microsoft’s AI Sowing App, developed in collaboration with ICRISAT, uses machine learning and weather forecasting to guide sowing decisions. Similarly, the Pest Risk Prediction API, co-developed with United Phosphorous (UPL), India’s largest producer of agrochemicals, alerts farmers about imminent pest attacks using AI algorithms trained on historical and satellite data.

An AI-powered policy push

India is among the first Global South countries to aggressively mainstream AI in agriculture. In 2024, the Government of India launched the IndiaAI Mission, earmarking ₹10,300 crore (~$1.25 billion) to build a robust AI ecosystem across sectors. Agriculture is explicitly listed as a priority sector under NITI Aayog’s National Strategy for Artificial Intelligence.

AI-powered mobile phone apps can help farmers to diagnose diseases afflicting their crops. (Photo by WESTOCK PRODUCTIONS/Shutterstock)

Reinforcing this commitment, the Digital Agriculture Mission pledged ₹2,817 crore (approx. $321.14 million), with ₹54.97 ($6.27 million) crore allocated for the 2025–26 fiscal year toward creating a “robust digital agriculture ecosystem in the country for driving innovative farmer-centric digital solutions.”

At the same time, India’s private sector is rising to the challenge. As of 2023, the country now hosts over 2,800 agri-startups, and has attracted ₹6,600 crore ($752.40 million) in private equity funding over the last four years. The top venture capital investments are led by firms like Omnivore, Blume Ventures, 3one4 Capital and BIRAC.

Equity and environmental questions

In principle, AI-enabled agriculture holds significant promise for advancing sustainability by boosting productivity, minimizing input waste, enhancing supply chain efficiency and strengthening farmers’ resilience to climate-related shocks. These technologies have the potential to transform agricultural systems by enabling data-driven decision-making, early warning systems and precision farming practices. However, despite these prospects, there remains a critical gap in independent and rigorous evaluations of their effectiveness, scalability and long-term impact, particularly in low-resource environments and linguistically diverse regions where infrastructural, cultural and educational barriers may hinder adoption and equitable access. Comprehensive studies are needed to assess not only the technical performance but also the socioeconomic outcomes and inclusivity of these innovations.

Currently, the major perils that trouble the AI-agri space are:

- Risk of exclusion: India’s AI-powered agriculture tools often default to English—a language spoken fluently by less than 10% of the population. This language barrier disproportionately excludes small and marginal farmers, particularly women, from reaping the benefits of AI-driven advisory systems. Designing interfaces in vernacular languages and accommodating low-literacy users is not a technical luxury—it’s a moral imperative.

- Data privacy and knowledge appropriation: With AI comes data—lots of it. But who owns this data? Farmers often contribute their data without informed consent, lacking clarity on how it will be used, monetized or protected. The absence of robust data governance frameworks risks the misappropriation of indigenous knowledge and disempowers local communities. Moreover, the corporatization of agricultural services via AI platforms could shift power from farmers to private intermediaries, who may begin to control everything from crop advice to credit access.

- Transparency: In agriculture, AI often functions as an opaque decision engine—a “black-box” issuing advisories or grading produce without providing much explanation of the background process. Transparency is required not only in making the underlying process (data, algorithm, model structure and parameters) publicly visible, but also comprehensible for the common person.

- Algorithmic bias: Rooted in human decisions and historical data patterns, algorithmic bias is often an unintended consequence of data collection and model design. As a result, it has the potential to perpetuate and amplify existing social and economic inequities. “Algorithmic bias in agricultural technology can unintentionally deepen existing disparities by prioritizing data from dominant farming systems,” says Sustainability Satellites. In particular, these large models need to be tailored or created keeping in mind its more context-specific use.

- Economic inequality and cost barriers: Many agri-AI platforms operate on a subscription or service-fee model. While profitable for startups, this raises questions about affordability for resource-constrained farmers. Will poorer farmers be locked out of precision agriculture’s advantages? If AI exacerbates existing inequalities in input access, it could further marginalize those who are already vulnerable.

- Labor displacement and gender impacts: AI’s efficiency may come at the cost of employment. Automation in post-harvest grading, sorting and even sowing could displace agricultural laborers, many of whom are women or landless workers with few alternative income options. Without parallel investments in skill-building and social protection, these workers could be left behind in the digital revolution.

- Lack of accountability: Most AI tools deployed in agriculture are not subject to independent audits. Their outcomes are seldom evaluated for fairness, inclusivity or unintended consequences. Without transparent mechanisms for monitoring, the sector risks becoming a digital black box—one that’s hard to govern or course-correct.

- Environmental footprint of data infrastructure: AI’s computational appetite is voracious. The massive energy demands of data servers and cooling stations needed to process AI workloads could offset the very environmental gains these technologies aim to deliver. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), global data centers consumed over 415 Terrawatt-hours (TWh) of electricity in 2024, which is predicted to increase to 945 TWh in 2030. That rise is predicted to increase even more rapidly with AI expansion.

Toward inclusive and accountable AI in agriculture

If artificial intelligence is to serve Indian agriculture, it must be shaped as a public project, not merely a private product. Today, much of the experimentation and deployment sits in the private sector and behind paywalls. This pricing and access model risks concentrating gains among better-resourced farmers and agri-businesses, thereby widening existing income and information gaps.

A different pathway is possible. Public leadership can set a direction for AI that is locally grounded and broadly shared—through India-trained models and open and well-governed datasets that enable low-cost tools. When coupled with strengthened public extension—training frontline workers to translate AI outputs into context-specific advice—these assets can convert digital promises into on-farm productivity, resilience and fairer markets. Treating core AI capabilities as public goods can lower the cost of access, crowd in innovation and ensure that benefits do not stop at corporate gates.

The choice is ours: build AI that works for every farmer or accept a digital future that leaves the most vulnerable further behind.

Equally, the innovation process must be democratized. Technologists cannot do this alone. Key knowledge partners like agronomists, rural development practitioners, economists, extension workers, farmer producer organizations, input suppliers and—critically—farmers themselves should be co-designers. Participatory development, multilingual interfaces and low-bandwidth, mobile-first tools are essential for uptake in diverse agro-ecologies and linguistic contexts.

Accountability must be built in from the start. Governments should mandate transparency on data governance and model design; require independent audits for bias, safety and field effectiveness; and protect farmers’ data rights through clear policies and legislation. Bridging the digital divide will also demand public investment in rural connectivity, digital literacy and localized content so that the least connected are not the last to benefit.

Inclusive design, public accountability and policy coherence are not optional features; they are preconditions for equitable impact. With decisive public stewardship and farmers as co-creators, AI can become the next layer of rural infrastructure, enabling productivity gains and climate resilience while narrowing, not deepening, inequalities. The choice is ours: build AI that works for every farmer or accept a digital future that leaves the most vulnerable further behind.

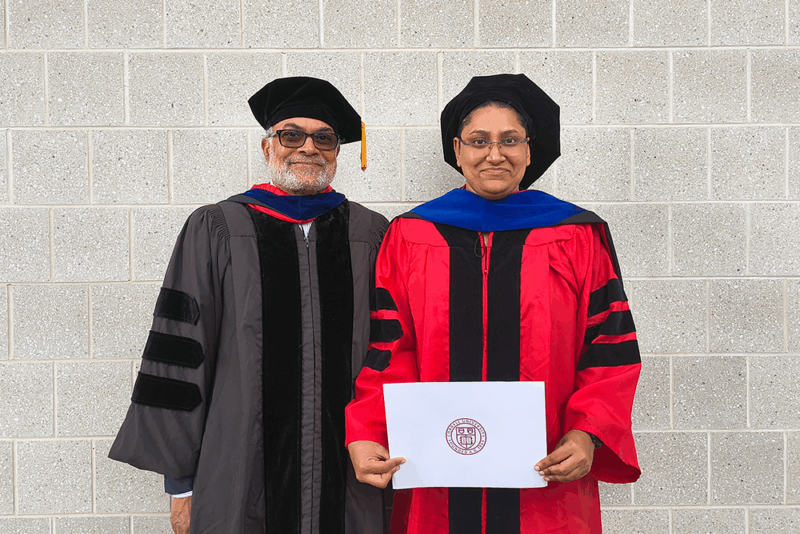

Shree Saha is a TCI alumna. She earned her PhD in applied economics and management in 2025.

Featured image: A drone flies over farmland. (Photo by Ira.foto.2024/Shutterstock)