Compiling better data on mycotoxin incidence and identifying control options: Utility of participatory research

Norman Borlaug, plant scientist and founder of the Green Revolution that shaped India’s modern agricultural economy, stated that “Food is the moral right of all who are born into this world.” I believe that it is also a basic right, that every individual should have access to foods that are not only plentiful but also safe enough to provide vital nutrition to consumers. Food rich in nutrients is a key to solving the complex problem of malnutrition globally.

However, unfortunately, in much of the developing world, one’s diet often bears harmful contaminants, like mycotoxins produced by fungi, which can compromise the ability of food to nourish the body and result in adverse effects on human and animal health such as cancer, nutritional deficits, and immunological disorders.

In the Indian context, not many are aware of mycotoxins and their potentially harmful effects, hence it is high time that the development sector works to mobilize smallholder communities against this threat. There is a growing need to generate awareness on locally-specific food safety needs, especially among farmers so that course correction can mitigate contamination effects.

| Collective action should be taken between the development sector and smallholder communities themselves to contain the risk of mycotoxin contamination for both economic and health reasons, as the risks extend not only to the farmer’s field and market value but also into the household food ecosystem. |

The challenge of mycotoxin management in resource-poor systems

A major constraint towards taking action on issues that jeopardize food safety in rural communities in India and elsewhere is the lack of meaningful, interpretable data that could enhance understanding of mycotoxins and drive positive actions. Owing to insufficient capacity for regulatory oversight and spatiotemporally-unbalanced sampling efforts, there is very little generalizable evidence from the village context to be leveraged in food safety interventions. The outcome of this information void has been either stagnancy in food safety innovation or deployment of often ill-fitting intervention schemes that lack local cultural resonance and palatability.

The Intervention

The TCI-TARINA program for mycotoxin management in household grain storage systems is guided by the philosophy that robust, locally-specific solutions to key food safety concerns must necessarily be co-created by stakeholder communities, which offer rich perspectives on local contexts that are vital for sustainable, accessible, and efficacious interventions. Moreover, engaging smallholders in the sampling and surveillance process serves dually to generate extremely high-resolution data on mycotoxin incidence and food spoilage phenomena, and also to enrich the community’s capacity to perceive and interpret trends, risk factors and dynamics in their grain storage ecosystem that can inform future innovations from the grassroots.

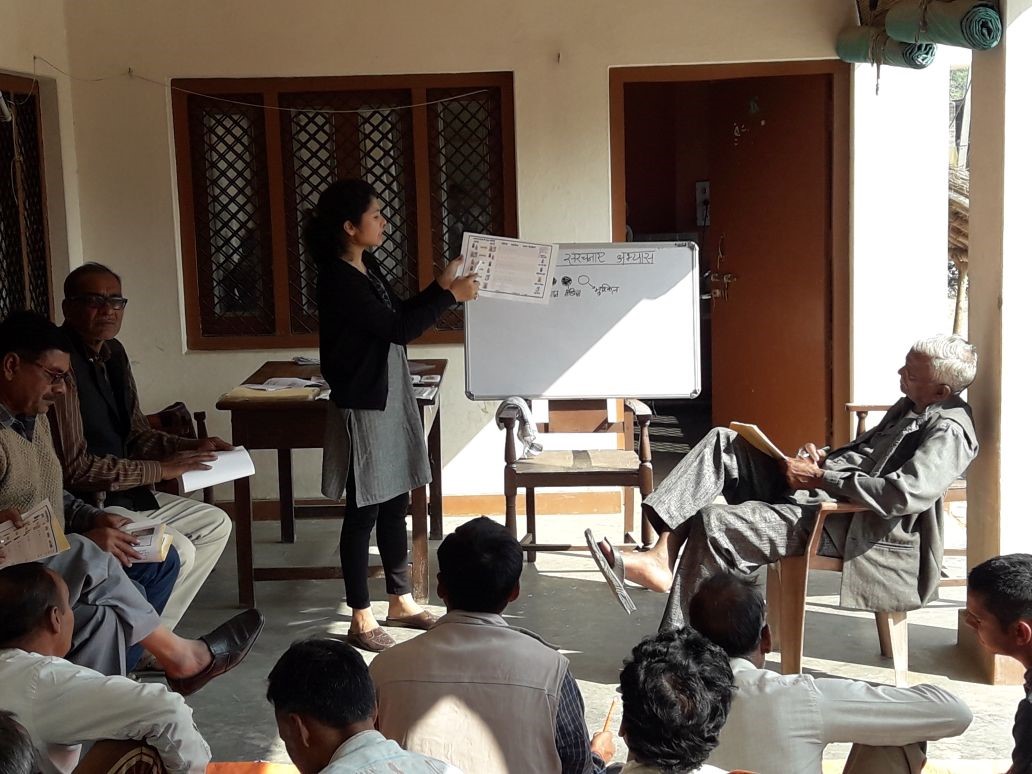

Combining scientific expertise with the local contextual knowledge to maximize problem-solving capacity and lead to desirable, sustainable outcomes (Photo Credit: Anthony J. Wenndt)

Over the past year, our participatory data collection programming has yielded to over 2000 data points on mycotoxin incidence and severity across a range of commodities, geographies, and grain storage environments that are powering meaningful inquiries on the intersections of organismal biology, ecology and physicochemistry that dictate toxin accumulation and food spoilage trajectories. Furthermore, our hands-on, household-level surveillance approach coupled with Participatory Action Research (PAR) activities in the target communities have elucidated intervention options that are both scientifically valid and tailored to the needs and resource constraints of the stakeholders

Participatory research for mobilizing communities on food safety

Here, I would like to share the example of the hermetic grain storage bag, which is a simple and affordable enhancement to the already-prominent sack-based grain storage regime in the targeted communities. The TCI-TARINA team and the farmers have identified these bags as a tractable solution to the demonstrable damage caused by invasive pests and microbes in the storage environment. At present 98% of households enrolled in the study have successfully adopted hermetic storage as an outcome of the participatory programming. Continued monitoring of the quality and safety parameters will enable us to refine the use of this technology (and others) to suit locally-specific needs.

Findings from the participatory research will be used as a foundation for scaled-up participatory research efforts in northern India

Participatory research has proven itself a powerful tool for mobilizing communities around food safety issues in rural India and it has enabled us to generate a data-set on incidence and intervention options that are not only scientifically robust but also is explicitly taking into account the locally-specific desires and limitations of the stakeholder communities – without which sustainable long-term amelioration and innovations would be impossible.

By Anthony J. Wenndt*

*Anthony J. Wenndt is a Ph.D. Student and a Tata-Cornell Scholar in the field of Plant Pathology and Plant-Microbe Biology. He is interested in the biology and ecology of toxigenic fungi infecting crop plants and the impacts of mycotoxins on food security and nutrition.