Field notes: Finalizing the research plan

Dr. Debbie Cherney, one of TCI’s Faculty Fellows and my committee chair, was graciously supported by TCI to visit India during Spring Break 2016. Dr. Cherney had never travelled to India previously, so this was an invaluable experience for her to observe India’s livestock systems. Lacking first-hand experience of India, she voiced that it was challenging to fully grasp the idiosyncrasies of project implementation here. Dr. Cherney flew into Bhubaneswar, Odisha, where my research will be based. During her one week, we met faculty at the Odisha University of Agriculture and Technology to speak about using their ovens for sample drying, met staff from CARE India that is supporting some of my fieldwork logistics, visited the nearby Ganjam District for a farmer training session, and had lengthy discussions about the feasibility of my planned research methods. Throughout the week’s discussions, we tentatively finalized my research plans, though I expect that my research design will be contextualized to the local scenario after speaking more with local farmers and goat sector stakeholders.

Dr. Cherney gets personal with some of our experiment clientele. (Photo credit: Maureen Valentine)

My current plan is to run an experiment in two villages of Kandhamal District in Odisha. In each village, there will be a control and a treatment group. The control group will contain goat farmers continuing with their traditional goat grazing patterns. The treatment group will contain goats fed in a semi-stall feeding system. The treatment group goats will go grazing in the morning, and return to their homes for stall feeding in the afternoon.

The reason we chose Kandhamal District is because this district has a majority population of Scheduled Tribes, which tend to be less literate and experience higher rates of poverty. Migration out of villages is common because there are few livelihood opportunities on their farms. In an effort to reduce migration, CARE India and other organizations are implementing initiatives to improve livelihoods locally. Goatery is one of the few livelihood opportunities already observed, and it is therefore logical to improve the productivity of goats with best management practices.

A tribal woman in the Burupati village of Kandhamal District, Odisha after leaving one of the focus groups organized by Tata-Cornell. (Photo credit: Maureen Valentine)

Understanding the underlying problem…

The main challenge with improving goat rearing is that many tribal people do not consider goats’ economic potential. Their main reason for rearing goats is to sell in times of emergency, but they are not considered a viable economic livelihood. Goats are interwoven into tribal people’s lifestyle and culture without much serious thought. In the same way that it is natural to get married and have children, it is natural to have goats. Mindsets around the use of goats must be augmented in order for goats to be reared in a more economically-sound manner.

Feeding has been viewed as the largest constraint to increasing the productivity of goats because in seasons with little vegetation (mainly summer) goats must walk long distances and expend their much needed energy to find forages. For small-scale goat farmers, productivity improvements are required to compete.

Additionally, Odisha is facing increasing degradation of their forest resources due to human and animal population pressure and industrial extractions. The question of how farmers will feed their animals if their common property resources become too degraded to sustain their animals, or if the Forest Department restricts access for the same reasons, is timely.

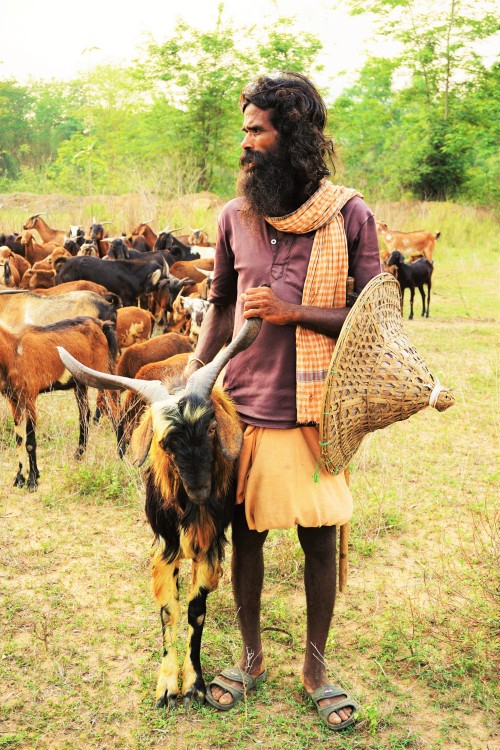

A herder in Ganjam District, Odisha shows off one of the larger bucks in his herd as they move towards other grazing options. (Photo credit: Maureen Valentine)

…and using research to learn how to address it.

During three seasons, we will measure the animal health (parasite load, body condition scoring, animal weight), animal nutrition (quality of different diets, feed intake), household costs, household labor, and estimate the biomass extraction from forest resources.

Research questions are as follows:

- What is the dry matter intake and ration digestibility of free-ranging goats in tropical Odisha?

- What are the goat physiological, health and nutrition differences between extensively grazed and semi-intensive systems?

- What are the income and labor implications for small farmers changing from extensive to semi-intensive livestock systems? What are the environmental and sustainability implications?

- Could the Small Ruminant Nutrition System be utilized for predicting dry matter intake and animal responses for free-ranging goats in tropical India?

I’m very appreciative that Dr. Cherney had the opportunity to come and see India and discuss my project in this preliminary phase. Next week, I’m planning to conduct focus groups with non-target villages. We will focus on farmer’s perspectives towards my proposed experiment and aspects where they may have reservations or objections. I can then amend the methodology or explanations to prepare for farmers’ reactions in target villages. I will be presenting my research proposal at an International Livestock Research Institute stakeholder meetings in May, which will be the final step before implementation.

By Maureen Valentine

Maureen Valentine (mev53@cornell.edu) is a TCI Scholar and a second year Ph.D student in the Department of Animal Science. Maureen is currently completing her one year of fieldwork as required for TCI Scholars. Her fieldwork will involve a goat feeding experiment in the Kandhamal District of Odisha State.