Understanding Chicken’s Ascendant Position on Indian Plates

It is a common misconception in the West that the people of India are all vegetarians. In fact, only 30% of the Indian population is vegetarian, a figure that varies significantly by region, caste and religion. Despite being home to the largest vegetarian population globally, India also has one of the world’s fastest-growing meat markets—particularly for chicken. This growth reflects not just rising incomes, but also a shift in dietary preferences and nutritional demands.

As incomes grow, the challenge of malnutrition in India persists. Chicken—affordable, rich in protein, and culturally more acceptable than beef or pork for many communities—is uniquely positioned to meet this nutritional need. Chicken consumption in India has grown significantly over the past 15 years. Rising incomes across the country have increased demand, but gaps in the value chain are hindering the industry from reaching its full potential. Chicken remains a luxury good.

The Indian poultry market is highly segmented. Around 90% of the market remains unorganized—dominated by backyard and smallholder poultry operations—while only 10% operates under modern, integrated systems. Organized players have better access to cold chains, logistics and health management systems, but remain limited in scale. Inadequate infrastructure, such as poor road networks, limited cold chain systems and insufficient storage facilities, contributes to waste throughout the chicken production process. These weaknesses in the supply chain make chicken affordable only for higher-income groups.

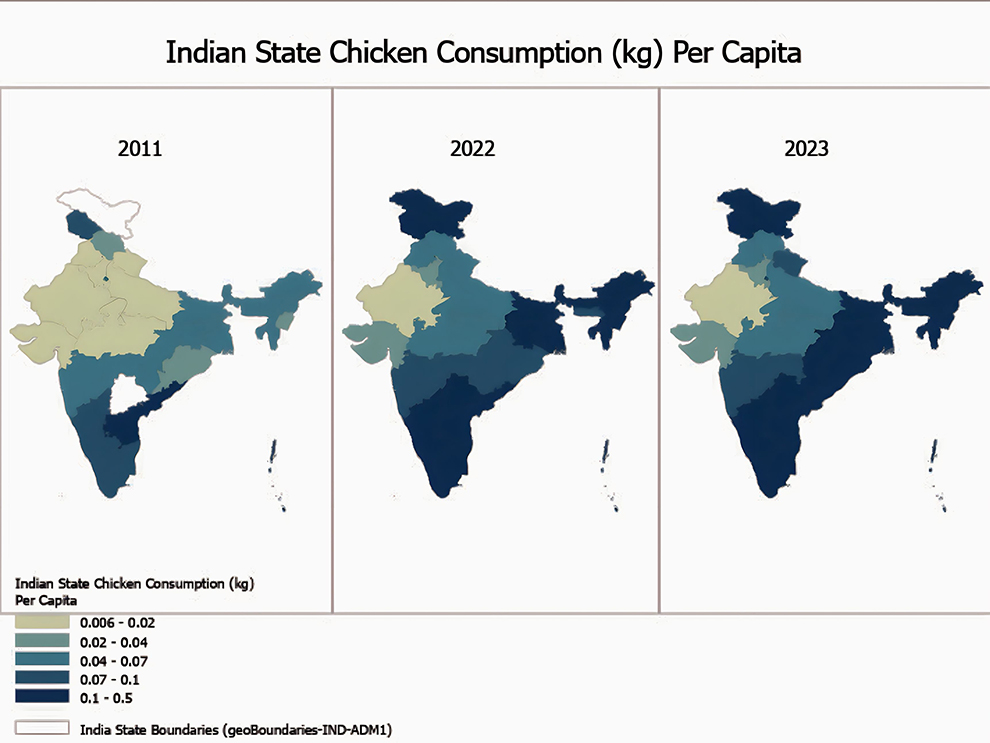

While chicken remains a luxury good, consumption data from the National Sample Survey (NSS)—now called the Household Consumption and Expenditure Survey (HCES)—from 2011, 2022 and 2023 indicates a steady increase in average per capita chicken consumption.

The expansion is broad-based, not limited to one region or income bracket. More importantly, the consumption gap between income groups is narrowing. In 2011, the poorest Indians consumed an average of 0.023 kilograms of chicken per person, while the richest consumed 0.09 kilograms. By 2023, those figures had risen to 0.071 kilograms and 0.122 kilograms respectively, reducing the deficit by 0.016 kilograms.

The expansion is broad-based, not limited to one region or income bracket. More importantly, the consumption gap between income groups is narrowing. In 2011, the poorest Indians consumed an average of 0.023 kilograms of chicken per person, while the richest consumed 0.09 kilograms. By 2023, those figures had risen to 0.071 kilograms and 0.122 kilograms respectively, reducing the deficit by 0.016 kilograms.

However, not all states followed this trend. In some outlier states, the poorest groups consumed more chicken per capita than richer ones, or the rich consumed more than the richest. In a few states, the gap between the richest and poorest exceeded 0.150 kilograms, while in others it was under 0.010 kilograms. These patterns suggest that consumption is not purely driven by income, but also by cultural, logistical and geographic factors. An analysis of these anomalies revealed no significant geographical patterns. Potential explanations—such as state legislation, infrastructure availability or the dominance of backyard over commercial farms—were not examined in the study. Further research into states with the smallest consumption disparities could offer insights into overcoming the luxury-good status of chicken. Nevertheless, the overall trend supports the idea that rising incomes lead to increased chicken consumption.

While income growth is more prominent in urban India, HCES data shows that the rural-urban consumption gap is narrower than expected. In 2023, average per capita chicken consumption was 0.090 kilograms in rural areas and 0.100 kilograms in urban areas.

This minimal difference may be attributed to the enduring strength of the unorganized backyard poultry sector. The One Health Poultry Hub, supported by the UK’s Global Challenges Research Fund, estimates that around 36 million Indian farmers continue to raise poultry in backyard systems—a vital practice for rural income and nutrition.

The narrow rural-urban consumption gap may instead reflect real increases in rural chicken consumption, rather than statistical misclassification. In 2011, rural chicken consumption was low across nearly all states, while urban areas in the South—such as Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh—showed relatively high consumption. By 2022 and 2023, however, rural consumption had increased substantially in many states, especially in eastern and central India. States like Bihar, Odisha and Chhattisgarh showed strong growth in rural consumption, narrowing the gap with their urban counterparts. In contrast, states like Gujarat and Uttar Pradesh still displayed much weaker rural demand, indicating that the convergence is uneven across regions. This suggests that rural consumers in several parts of the country are increasingly accessing and affording chicken, potentially due to better supply chains, rising incomes or cultural changes.

So, what lies ahead for India’s chicken industry? The most critical challenge is to improve infrastructure, whether through upgrading roads or expanding cold chain systems. Without these improvements, the already vulnerable broiler sector faces heightened health risks due to disease-prone intensive farming conditions. Increased investment in research and development could help reduce disease transmission, improve logistics and cut industry waste. Still, the thriving backyard poultry sector remains a valuable asset for rural India—enhancing both livelihoods and nutrition. If integrated with improved veterinary care and feed supply, backyard poultry can complement organized production in expanding protein access across socioeconomic divides.

Max Falkin was a TCI intern in the summer of 2025. He is a senior at the Cornell University College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, majoring in interdisciplinary studies with a concentration in applied economics.

Featured image: Chicken occupies a growing position in Indian diets. (Photo by Zosia Szopka/Unsplash)