Urban Farms Co. and the Potential for Social Enterprises to Catalyze Food Systems Change

Today, 56% of the global population resides in urban areas. This proportion is expected to increase to 70%, with the change driven largely by Asian countries. In India alone, it is estimated that by 2050 the number of people living in urban areas will increase by 416 million people. This rise in urban populations will lead to an increased demand for food in these areas and a shift towards more diversified diets. At the same time, climate change continues to pressure food systems with increased natural disasters and extreme weather events. In this dire position, we need to rethink the ways in which we are growing and distributing food. This is the challenge that Urban Farms Co., a social enterprise in India, is tackling.

This past summer, I spent a month with the Urban Farms team and their partner farmers learning about the potential ways in which social enterprises can facilitate food systems change. As a social enterprise, Urban Farms Co. adopts a business model that not only seeks to be financially self-sufficient but also leads with a mission to improve India’s food system. The company is dedicated to growing vegetables using practices that regenerate degraded soils while providing peri-urban farmers with a secure market to sell their harvests. Their mission was brought to fruition through the establishment of farm hubs across five locations: New Delhi, Pune, Nawalgarh, Hyderabad, and Solan. The hubs serve not only as centralized procurement centers but are also outdoor research labs for developing localized, context-specific regenerative practices for farmers.

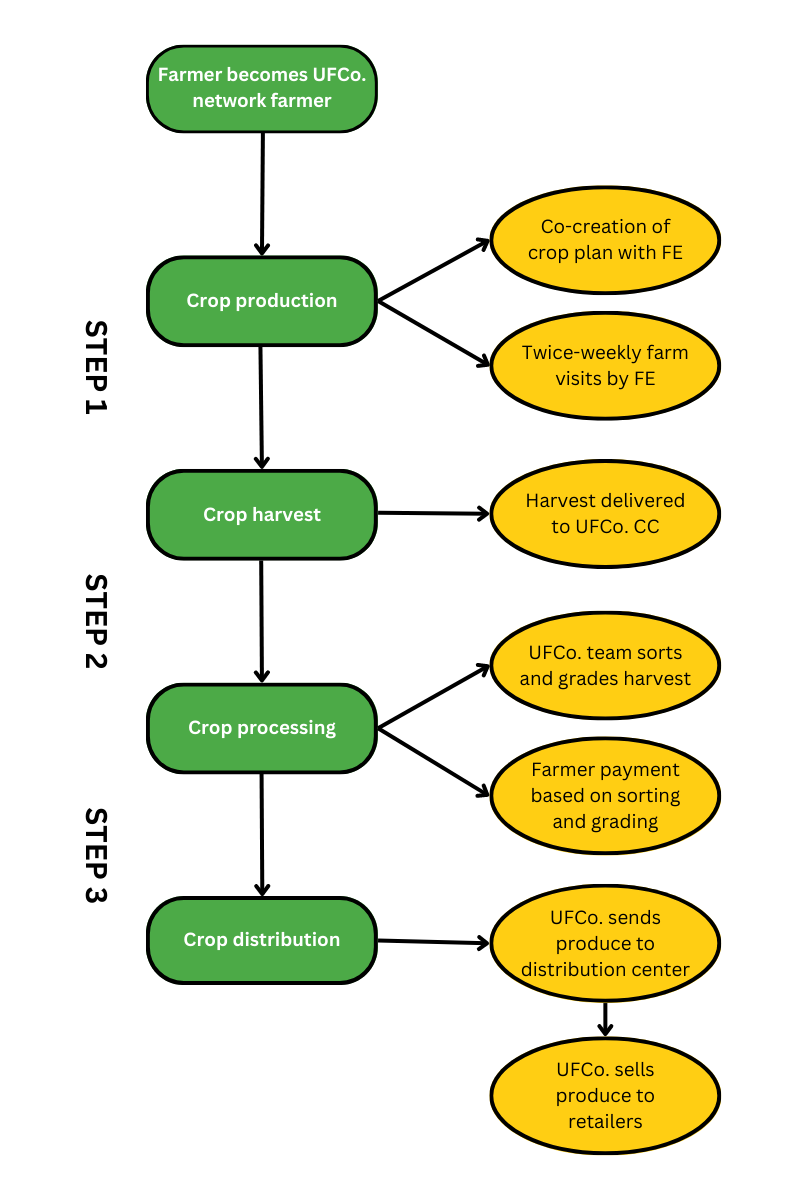

Unlike other food system interventions, Urban Farms Co. differentiates itself in the way that it supports its network of farmers throughout all stages of production, from planning to distribution. Below is a general description of the flow of production at an Urban Farms Co. Hub divided into three primary steps:

Urban Farms Co. Flow of Production

Step 1: New and existing network farmers meet with a field executive to develop a production plan for the season. This involves deciding on the acreage and crop that the farmer wants to grow in partnership with Urban Farms Co. Due to initial hesitancy and trust building, in their first season with the company, farmers usually choose only a portion of their land and 1-2 crops to grow with Urban Farms Co. Once this is decided, the field executive develops a season plan for the crop, calculating cost of production and estimated profit. Following this, the field executive visits the farmer’s land at least twice a week for the entirety of the season. During these visits the field experts assess the health of the crop and, if any issues arise, support the farmer in addressing them using regenerative practices.

Step 2: When the harvest is ready, farmers transport vegetables from their fields to Urban Farms Co. Collection Center. At the Collection Center, the Urban Farms team sorts and grades the vegetables into two categories: A and B. Farmers are paid a premium (25% of market prices at the Delhi Hub) for their A-grade harvests, while B-grade harvests are usually bought at lower than market prices. B-grade harvests are currently only bought from farmers at the Delhi hub. The farmer waits until the sorting and grading is completed and receives a receipt with their expected payment At the end of each week, farmers are paid the total of their receipts from all their harvests.

Step 3: Next, Urban Farms Co. sends farmer harvests to their distribution center. Here, vegetables are sorted and graded once more to ensure the highest quality for their retailers. B-grade vegetables are sold at the local mandi.

Room For Growth

Urban Farms Co. serves as an example of the potential ways in which social enterprises can intervene in the food system to address both the immediate (e.g. access to fair pricing, farm inputs, infrastructure, spaces to exchange knowledge) and long-term (e.g. healthy soils, access to diverse fruits and vegetables) needs of the peri-urban farmer and urban consumer. Yet, there are limitations within Urban Farms Co.’s framework.

Given that Urban Farms Co. works primarily by establishing hubs in the peri-urban regions of major cities, they must reckon with the long-term reality of urban sprawl. As cities face rapid growth in the coming years, peri-urban farmers are vulnerable to land grabs. The loss of agricultural land not only signifies the loss of space for food production but also the loss of essential ecosystem services that ecological agriculture offers. This raises the question of how a social enterprise like Urban Farms Co. can serve as an advocate for peri-urban farming as a critical function for urban populations and protecting farmer livelihoods and agricultural land. Addressing this question opens opportunities for relationship-building between private companies, the government, and the nonprofit sector.

Crops are sold at the Azadpur Mandi in New Delhi. (Photo provided)

Second, there is a greater need to address Urban Farms Co.’s responsibility for equitable food systems change. While their current system promotes higher purchasing prices for farmers along with sustainable production, questions remain about farmer experiences across demographics and locations. For example, while many farmers I spoke with were content with Urban Farms Co.’s pricing, one woman who worked on her husband’s farm shared that while they have received better prices for their harvests it still does not account for the increased labor required when using regenerative practices. This points to the differentiation between the benefits the farmer reaps under this framework versus the benefits to farm laborers.

The conversation around improving farmer incomes and livelihoods must be broadened to include farm laborers, who are often women. In the same way that Urban Farms Co. is able to nudge their partner farmers to adopt regenerative practices, can they also nudge them toward more fair labor practices?

There is also the consideration of equitable access for urban consumers. Historically, rapid urbanization has led to an unequal divide of opportunity and resources, increasing inequality. The challenge of feeding urban populations then becomes more nuanced. It is not simply about feeding more mouths, but meeting the food needs of a population that has varying access to food based on external, compounding factors such as employment, infrastructure, and healthcare.

Under the Urban Farms Co. framework, it is important to question who the food is being grown for and who it is actually going to. Currently, Urban Farms sells 60% of its produce to e-commerce companies. While e-commerce offers lower prices for the consumer in the short term, they pose a long-term threat to equitability as they monopolize the food market. As the company progresses it may be more beneficial for the consumer and the farmer to identify other modes of distributing produce that also shorten the supply chain.

These limitations do not serve to undermine the progress that Urban Farms Co. has been able to make in the space of food systems change, nor the potential for other social enterprises to do the same. Rather, they highlight the areas in which tensions exist and conversations must be had not only internally as a company but between stakeholders in various sectors. Urban Farms Co. has demonstrated how social enterprises can bring influential change if there is a continued commitment to equitability along the entire system. Social enterprises alone will not mend the failures within the food system but can provide a new avenue to enact direct change and serve as a bridge between stakeholders.

Alexandra Mantilla is a Cornell University student who interned with TCI during the summer of 2023 as part of the CALS Global Fellows Program.

Featured image: Alexandra Mantilla interviews farmers during her internship. (Photo provided)