What are the obstacles and opportunities in rural areas to achieving a “Cashless India”?

On 8 November 2016, India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi issued a demonetization policy not only to eliminate black currency, but also to promote a digital and cashless economy. The “Cashless India” and “Digital India” initiatives propose to reduce corruption at all levels of society by enforcing the use of cards, checks, or mobile phones for all transactions.

To set the stage for a “Cashless India,” Modi launched the Jan-Dhan Yojana (JDY) scheme in August 2014, which allowed all Indians to open bank accounts free of charge and with zero balance. After eliminating monetary constraints to banking, the government required citizens to have an Aadhar card (unique identification card) to receive rations from the Public Distribution System (PDS).

The result of these initiates is the formation of Jhan Dhan-Aadhar-Mobile, or “JAM” trinity, which links bank accounts, Aadhar cards, and mobile phones. The goal of JAM is to reduce inefficiencies and leakages in the PDS. More importantly, the government expects JAM to set the stage for a transition from the provision of food grains through the PDS to direct cash transfers, a heavily debated policy shift.

The radio, television, banks, telecom service providers, and government are promoting “Digital India,” even among farmers in rural areas. However, several infrastructural and behavioral barriers to carrying out this vision still remain.

Tools and services in a cashless economy

According to the “Digital India” initiative, there are several cashless transaction tools and services, some of which are relevant to the rural poor. The most obvious is a bank debit card or credit card, such as a Visa or MasterCard. Another tool is a pre-paid bank card, which is similar to a gift card with a certain amount of money on it. Pre-paid bank cards are commonly used by companies to dole out salaries to a large number of employees.

Mobile phones and the internet, platforms for online transactions and banking, are also major tools in a cashless economy. Internet banking, or Netbanking, is one type of online service, but there are also a number of mobile applications. Each bank has a United Payments Interface (UPI) application, which allows customers to transfer money easily between multiple bank accounts. Additionally, there are mobile wallets such as PayTM, Freecharge, Jio Money, etc., which link to customers’ bank accounts directly. Most recently, Modi has launched the Bhim application, based on the UPI, which allows instantaneous transfers between bank accounts.

Catering to the rural crowd, there are a few services that help people in remote areas receive or make payments. One is a micro-ATM, a handheld device, which costs far less to set up than a regular ATM and allows customers to make a range of transactions and transfers, as well as withdrawals. Another is the Aadhar Enabled Payment System (AEPS), which allows people to make a transaction at a micro-ATM or any other Point of Sale (PoS) machine with their Aadhar card. Post offices are also available for banking services. Finally, there is the Unstructured Supplementary Service Data (USSD), where a person can dial “*99#” on any basic mobile phone to inquire about their bank balance or even transfer funds.

Exploring the ground-level realities of a cashless economy in rural India: Lessons from Bihar

In late March 2017, only a few months after India’s demonetization and related reforms, I had the opportunity to visit the Munger District of Bihar, one of four district locations where TCI is working to implement its Technical Assistance and Research for Indian Nutrition and Agriculture (TARINA) project. The purpose of my visit was to investigate the ground-level realities of a cashless economy in a rural part of India, including the feasibility of cashless transactions and the penetration of cashless tools.

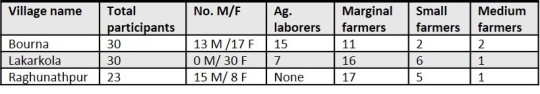

During my field visit, I conducted exploratory research through focus group discussions (FGDs) with agricultural laborers, as well as farmers with marginal, small, and medium plot sizes in three villages within Munger’s Dharhara Block: Lakarkola, Bourna, and Ragunathpur (see the table below for more details). Lakarkola is a predominantly tribal, or Adivasi, village, while Bourna and Ragunathpur consisted of mixed castes. The average respondent age was 40.

Gender and primary occupation of FGD participants

Across the board, all respondents reported having bank accounts and Aadhar Cards. Very few complained that distance to the bank is a problem. On average, the closest bank or ATM is about three kilometers away.

Respondents reported that instead of ATM cards, they mainly use bank passbooks to withdraw cash from their accounts. This problem is likely to be resolved with the younger generation. Some farmers indicated that their children help them with all bank related matters, which may enable them to eventually learn the new system for using ATM cards.

Most respondents indicated that their transactions are still entirely in cash. The only exception are cashless payments received from the government for their wheat or rice, which are directly deposited into their bank accounts. However, many complained that these payments are often very late.

Although all respondents claimed to have bank accounts, very few reported using mobile phones for banking or making payments. Unlike in urban areas, where shopping and paying bills can be conveniently done online using a smartphone, it appears that people in rural areas still find it more convenient to use cash. Moreover, some respondents perceived a “Cashless India” or “Digital India” as only relevant to people who are educated enough to use mobile phones or who make transactions with large sums of money.

“Only those who are literate and have knowledge of computers use things like digital payments, or only those who have enough money,” said an older agricultural laborer in the Bourna Village.

Despite this observed resistance to cashless transactions, it is important to note that my interactions in the field were primarily with older generation farmers. I did notice that the younger generation is starting to integrate cashless tools into their everyday life. In fact, it was apparent that younger women and men know how to use mobile phones and mobile wallets, while the older generation seemed neither interested nor aware of the possibility of linking their mobile phones to their bank accounts.

Constraints to the adoption of the Kisan Credit Card (KCC) system: An issue of discrimination based on landownership

Another important cashless tool and service available to farmers under “Digital India” is the Kisan Credit Card (KCC) system. A scheme that has been in place far before the Modi Government, the KCC is a process by which farmers can get loans at low interest rates and insurance for agricultural activities. In 2016, Modi stated that all Kisan Cards would be converted into RuPay Credit Cards and would look like ATM bank cards, further expediting the transition to a “Cashless India.”

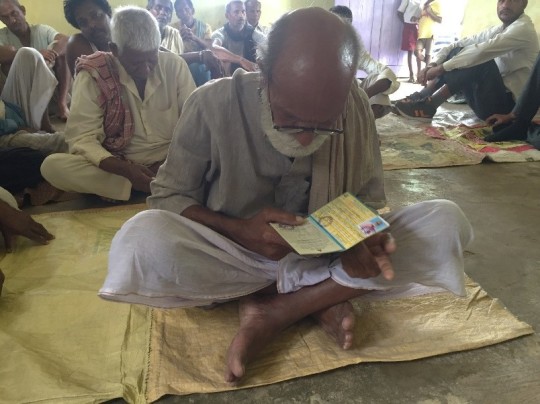

However, in Bihar most Kisan Cards were still in the form of a booklet, as farmers had not yet received their credit cards. In fact, only two farmers with medium-sized plots in Ragunathpur Village had Kisan Cards. One farmer, pictured below, received a loan to hire agricultural laborers and lease additional acres of land. A spritely, energetic old man, he had zeal for his work and was active in the community. He mentioned attending many town meetings and frequently speaking with local officials to ensure that Ragunathpur Village gets all the benefits that the government is proclaiming to bestow.

A farmer examines his Kisan Card details in Ragunathpur Village, Munger District, Bihar (Photo credit: Vanya Mehta)

“Anyone can get a Kisan Card if they want it,” the farmer said. However, when asked why nobody else has it, he responded, “People in this area just don’t want loans.”

He also explained that crop insurance may be purchased through the KCC, but the insurance companies often do not honor the claims. Furthermore, he stated that many farmers are unlikely to get a KCC because they know that banks will not support a loan or insurance program unless their landholdings are large enough. He has six acres of land, while many of the other respondents have only one to two acres, or even less. A few marginal farmers confirmed this statement, as they claimed to be rejected by the bank when applying for a KCC.

The role of local shops and traders in achieving a cashless rural India

In all interviews conducted during my field visit to Bihar, limited use of micro-ATMs among local shops, particularly among agricultural input shops, was reported as a constraint to the development of a cashless economy. While literacy may be a barrier to adoption, it is imperative for shop-owners to take up cashless tools so they are available to locals. However, poor internet connectivity and unreliable electricity may prevent their widespread installation and use in rural regions.

Traders also play a critical role in the shift to a cashless economy, but face a different set of constraints when adopting cashless technologies. For example, in the case of the electronic National Market (e-NAM), a mandi official interviewed in a recent article in Live Mint stated:

“Electronic trade has not kicked off as traders like to physically inspect the produce before they purchase, and farmers are usually reluctant to sell to traders in distant mandis due to fear of payment defaults.“

Looking ahead…

It is abundantly clear in today’s India that participation in government programs requires linkage to banks. Other cashless tools and services (i.e. mobile phones, Bhim apps, etc.) seem to be additional and helpful to those making frequent transactions or money transfers.

The future of the Modi’s “Cashless India,” nevertheless, lies in the hands of the rural youth. Although I did not interact with a sufficient number of young people in Bihar, those who I spoke to were smartphone literate and tech savvy. As they drive the transition to a cashless economy, barriers in rural areas will become less relevant, such as the perception that cash is safer to use or the issue of literacy.

However, in order to bridge the gap, the government will also have to respond with more efficient and timely delivery of payments to farmers, as well as infrastructural support in the form of micro-ATMs and reliable electricity.

With the help of infrastructure development and the burgeoning, digitally savvy youth in India, the possibility of achieving a cashless rural India may very well be conceivable in the coming years.

By Vanya Mehta

Vanya Mehta (vm335@cornell.edu) is a Research Specialist at TCI’s TARINA Center of Excellence, based in New Delhi, India.