Biorefinery to Kitchen: Addressing Iron Deficiency Using Microalgae-Fortified Flour

This piece from the TCI 2019-20 Annual Report presents TCI scholar Rohil Bhatnagar’s efforts to fortify wheat flour using iron from microalgae. Download the full annual report to read more.

Few foods are as appealing as freshly made roti. What if that roti were fortified with iron, a mineral that performs a critical function in the human body? It could help tackle a nutritional disorder that afflicts more than 600 million people in India, with tragic long-term consequences. TCI is exploring an innovative approach to curbing iron deficiency by fortifying wheat flour, using a byproduct of the biofuel industry.

Iron is a key nutrient involved in the synthesis of hemoglobin, which allows red blood cells to carry oxygen. Low iron levels in the blood, or iron-deficiency anemia, can cause impaired cognitive function and delayed physical growth in children, as well as long-term reduced working capacity. India has high rates of iron-deficiency anemia and pays a steep price for it in terms of mortality, disability, and lost productivity.

Fortifying staples like wheat with iron has long been considered a cost-effective public health approach to reducing iron deficiency, but ideal, bioavailable sources of iron that can be effectively utilized in food products have proven elusive.

TCI scholar Rohil Bhatnagar is working to change that. He is leading an effort to use defatted green microalgae called Nannochloropsis oceanica, a byproduct of the biofuel industry, as a novel source of iron. With 3,530 mg of iron per kg, the microalgae compare favorably to other iron sources in terms of bioavailability, which means more of it can be absorbed and used by the body.

Fortifying flour with iron can help make commonly consumed foods like roti more nutritious. (Photo by Nadir Hashmi CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

The bioavailability of microalgae was confirmed in a TCI lab study conducted with iron-deficient mice. Mice that were fed a diet that included microalgae-extracted iron had improved hemoglobin levels and a two-fold increase in iron storage in the liver, compared to an iron-deficient control group.

Bhatnagar also conducted a safety assessment study of continuous microalgae consumption, since having excess iron in the body has been shown to have adverse health effects. In the study, mice fed high levels of microalgae did not experience any negative effects, such as oxidative stress, iron bioaccumulation, or inflammation.

After determining the safety and efficacy of microalgae as an iron source, Bhatnagar conducted household surveys, focus group discussions, a village-level market assessment, and interviews with local medical practitioners in Gujarat, Jharkhand, and Bihar, India, to determine the ideal food for fortification. Because wheat flour is widely consumed and available through the Public Distribution System in India, it was selected as a potential vehicle.

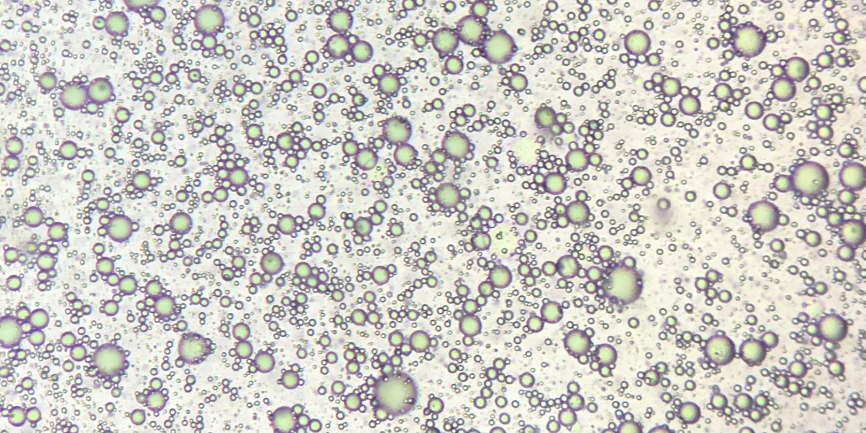

However, an important challenge remained. The microalgae have an unattractive green color and unpleasant fishy aroma that could be very unappealing when added to roti. Additionally, the interaction between iron and lipids present in the wheat flour may cause undesirable color changes over time. To overcome these challenges, Bhatnagar encapsulated the microalgae in water-in-oil-in-water emulsions using conventional homogenization. Microcapsules, developed using this technology, enabled flour to be fortified without unwanted colors or smells and were also stable at temperatures typically used to bake bread like roti (~220°C/430°F).

This work provides a novel approach to combatting global iron malnutrition and exhibits the vast potential of microalgae as an effective and safe source for fortification. Current and future work is focused on assessing shelf-life changes in microalgae-fortified wheat flour. A sensory study will also be conducted to assess any significant differences between fortified and unfortified roti.