Can Bihar’s Agricultural Sector Go Climate-Smart?

In mid-August, I traveled to Bihar, India as part of a team of researchers from the Tata-Cornell Institute for Agriculture and Nutrition to study strategies to reduce the greenhouse gas emissions associated with agriculture. With the trip scheduled during monsoon season, I was prepared to spend most of my time soaked from the rains. It is perhaps fitting, then, that on a research expedition concerned with the relationship between agriculture and climate change, the monsoons were late, and I stayed mostly dry.

Monsoon season determines who will thrive and whose crops will suffer, and climate change is interfering with those weather patterns. This year, the monsoon season in Bihar was delayed, which resulted in an enormous deficit of water needed for rice transplantation, leaving vast areas of land uncultivated. Yet excess rain in neighboring Pakistan submerged one-third of the country, killing thousands, causing more than 700,000 heads of livestock to be lost, and damaging more than 3.6 million acres of crops.

Making Indian agriculture zero-hunger, zero-carbon

Such a reality could continue and even get worse if climate change is allowed to continue unabated. Though most of agriculture stands to suffer in a warming world, it also contributes to that warming through greenhouse gas emissions. This is a particular problem for countries like India that must intensify farming to feed growing populations. That is why TCI embarked on the “Zero-Hunger, Zero-Carbon Food Systems” (ZHZC) project, which aims to provide policy options for reducing agricultural emissions in Bihar while improving production.

My visit was part of the second phase of the project. The first phase included a high-level expert workshop, which took place in April 2022 in Delhi. There, expert researchers in crop and livestock production discussed different high- and low-level interventions to increase food production and at the same time to reduce emissions. The next phases of the ZHZC project will include scenario building and modeling, as well as the dissemination of our findings.

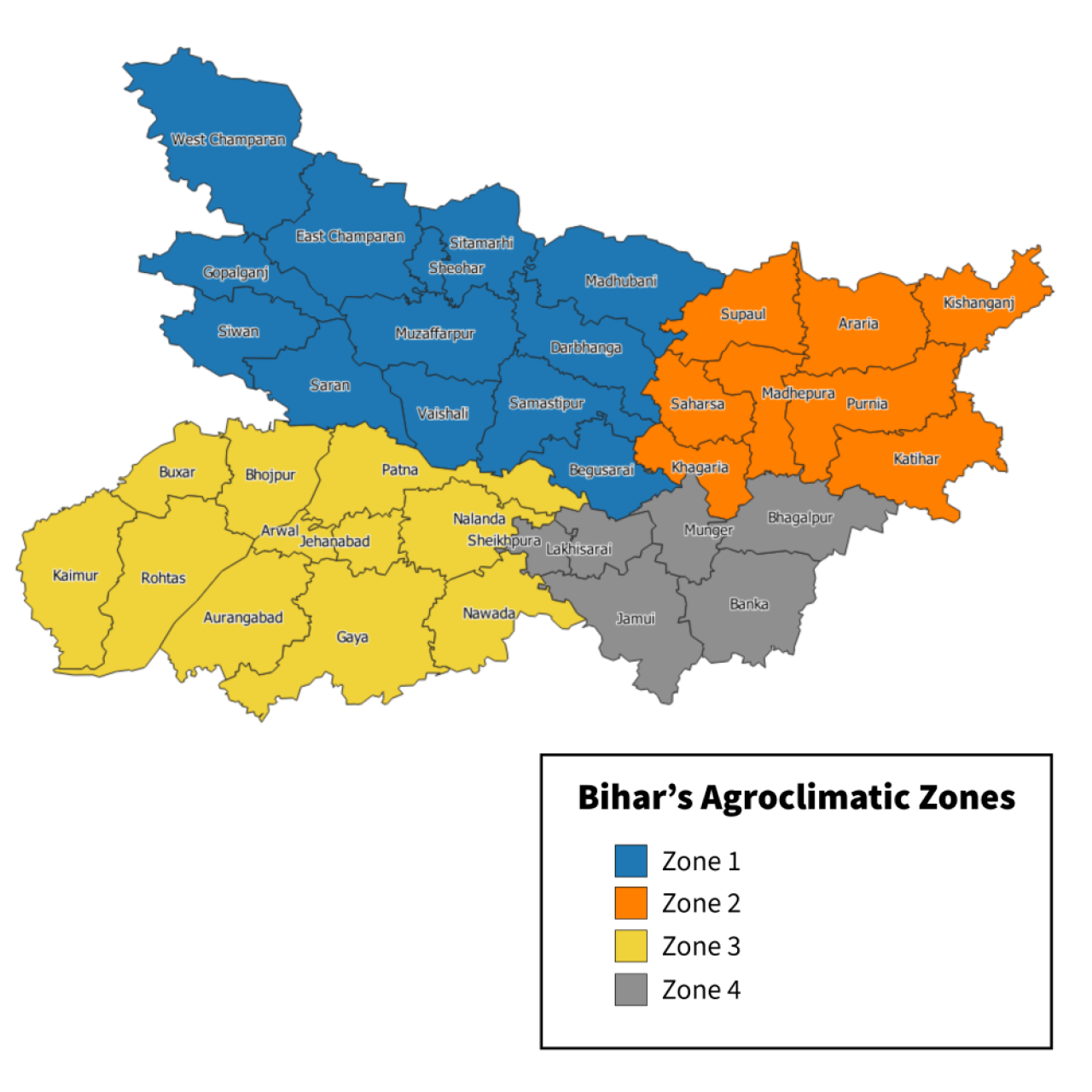

The purpose of the second project phase was to confirm ideas discussed during the expert workshop, to better understand current agricultural practices on the ground, and to hear farmers’ opinions on the relationship between climate change and agriculture. To that end, we spent about three weeks traveling between Bihar’s agroclimatic zones, talking to male and female farmers, researchers, and extension workers.

We first visited Nalanda district in Zone 3, then moved to Zone 1 where we visited Vaishali, Samastipur and East Champaran District. We then moved to the east and stayed in Purnia district in Zone 2 for a couple of days before finishing our trip in Zone 4’s Munger district. After three weeks and almost 1,800 miles traveled, we learned much about agriculture and attitudes toward climate-smart practices in Bihar.

Farming practices throughout Bihar

While there are many similarities between the four agroclimatic zones, there are many differences when it comes to agricultural practices. I found it incredible that the differences in the composition of cow breeds between zones was so clear. While on Zones 1, 3, and 4, farmers raised a balanced mix of indigenous and crossbreed cows, Zone 2 was heavily dominated by the indigenous breeds. In the context of lowering emissions, these differences matter because the milk production of indigenous breeds is much lower and emissions per liter are higher.

As for the areas under cultivation, Zone 4 was unique for its numerous patches of uncultivated land. This was caused by the late arrival of the monsoons, leaving a dearth of areas under water where rice could be transplanted. I did not notice this in other zones. While rice and wheat are major crops in each zone, there was substantial sugar cane production in Zone 1 and equally substantial jute production in Zone 2. These two crops are barely visible in the other zones.

In addition to differences between the zones, there was also a stark difference in production and consumption patterns among villages closer to towns and cities and those that are isolated and disconnected from official market channels. Those closer to the market designed their production for both home consumption and for the markets, while those who are isolated mainly produce for their own consumption.

Farmer attitudes toward climate-smart agriculture

Some of the villages we visited in Bihar had been part of past climate-smart agriculture projects. Unsurprisingly, there was much more awareness and knowledge of climate change among farmers from those villages than in others. Awareness was very limited among those who were never part of any program. All farmers, however, said that agriculture does not affect climate change, but that the opposite was true.

As for climate-smart practices, some proved to be more accepted by the farmers, like zero-till rice production, and artificial insemination of livestock. Others were less accepted, like biogas collection and zero-till wheat production. There are several determinants of the adoption of different technologies. The main one is the economic aspect—will the intervention lead to a reduction in input costs and will it increase productivity? Another important component is whether the technical preconditions can be met. In case of directly seeded rice, the plot should be big enough for machinery use and it should be under controlled irrigation, as soil moisture is one of the main determinants of successful sowing.

We also visited several sites where solar irrigation pumps are being used, but those investments were made through research project activities and would be prohibitively expensive for smallholders to use on their own.

A parting reminder of the links between agriculture and climate

The findings from our field assessment, along with ideas discussed during the expert workshop, will be used in the next phase of the ZHZC project, scenario building.

Even though we had come to Bihar during the rainy season, our trip was notable for its lack of precipitation. It was a bittersweet feeling. On one hand, I was pleased that we managed to finish the trip as planned, but on the other hand, I was keenly aware that millions of farmers depend on this monsoon season, and their crops were decimated.

It was only on the very last day of our trip, after we finished our final interview, that thick gray clouds began to gather and the rain finally arrived. As the level of the Ganges started to rise, I hoped that it would bring some relief to Bihar’s farmers.