Farmers and Consumers Pay the Price for Burdensome GM Regulations: The Case of GM Mustard in India

Policymakers in India have taken the first step to allow commercial cultivation of genetically modified (GM) mustard. The conditional approval for the environmental release of the Dhara Mustard Hybrid (DMH)-11 and its parental events bn3.6 and modbs2.99, given by the government in October 2022, signifies a shift in a policy stance held for more than a decade after a moratorium on GM crops was imposed in 2009. GM mustard could become the second biotech crop in India after Bt cotton and the first such food crop to enter farmers’ fields if it can pass the additional hurdles of seed multiplication, post-release monitoring tests, and ongoing litigation in the Supreme Court of India.

Rapid discoveries in biotechnology provide new technological options to increase production and make food systems more sustainable. Despite the availability of novel technologies, smallholder farmers in developing countries are denied the benefits of rapid discoveries in biology due to the misinformation campaigns and excessive regulation premised on a ‘precautionary approach.’ There is wide agreement among economists that optimal regulations related to food and environmental safety should be based on cost-benefit analyses coupled with distributional consequences. Excessive regulation and uncertainty about commercialization stifles research and investments, leaving society worse off with sub-optimum utilization of biotechnology.

The case of GM mustard in India typifies this scenario and has been in limbo for more than a decade. In a study published in The Economic and Political Weekly in October 2023, we analyzed the rationale, safety of technology for food and environment, yield gains, and cost of regulatory delay in this blog post. Our study reveals that GM technology enables mustard hybrids with higher yields, poses no risk to food and the environment, and benefits farmers and consumers through higher farm incomes and lower vegetable oil prices. Our conservative estimates show that the Indian farming community lost additional income gains worth USD 16 billion, while the country lost 15-20 million tons of mustard seeds.

Why genetic modification technology?

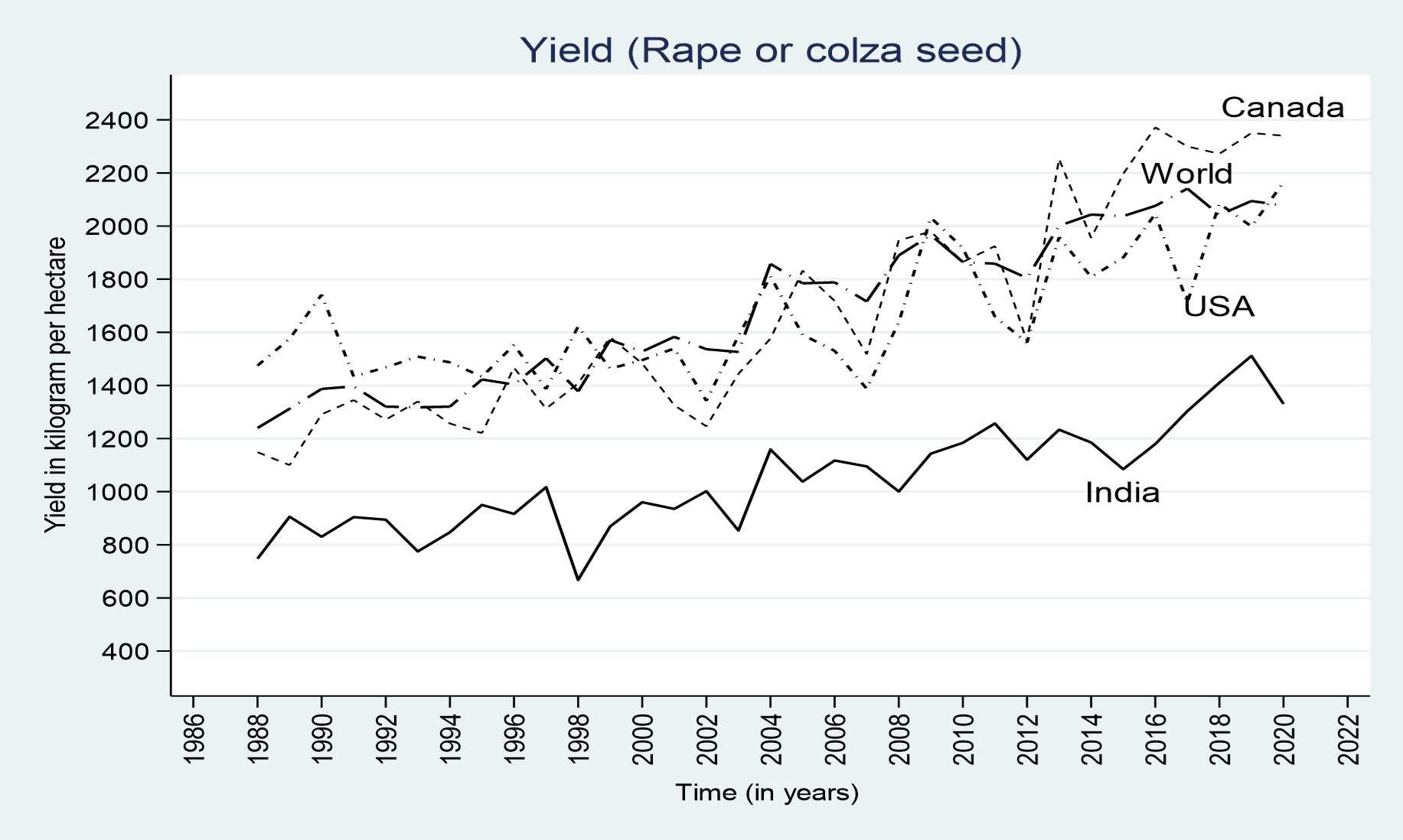

The history of crop production reveals the pivotal role of hybrids in improving yields, increasing farmer profits, and reducing poverty. Leading oilseed producers, namely Canada, the US, the European Union (EU), and China, shifted from open-pollinated rapeseed varieties to hybrids and subsequently broke yield barriers. In comparison, India’s yields of mustard and other oilseeds have increased much more slowly.

Mustard yields in India vis-à-vis other countries (Kgs/Ha)

Source: FAOSTAT data

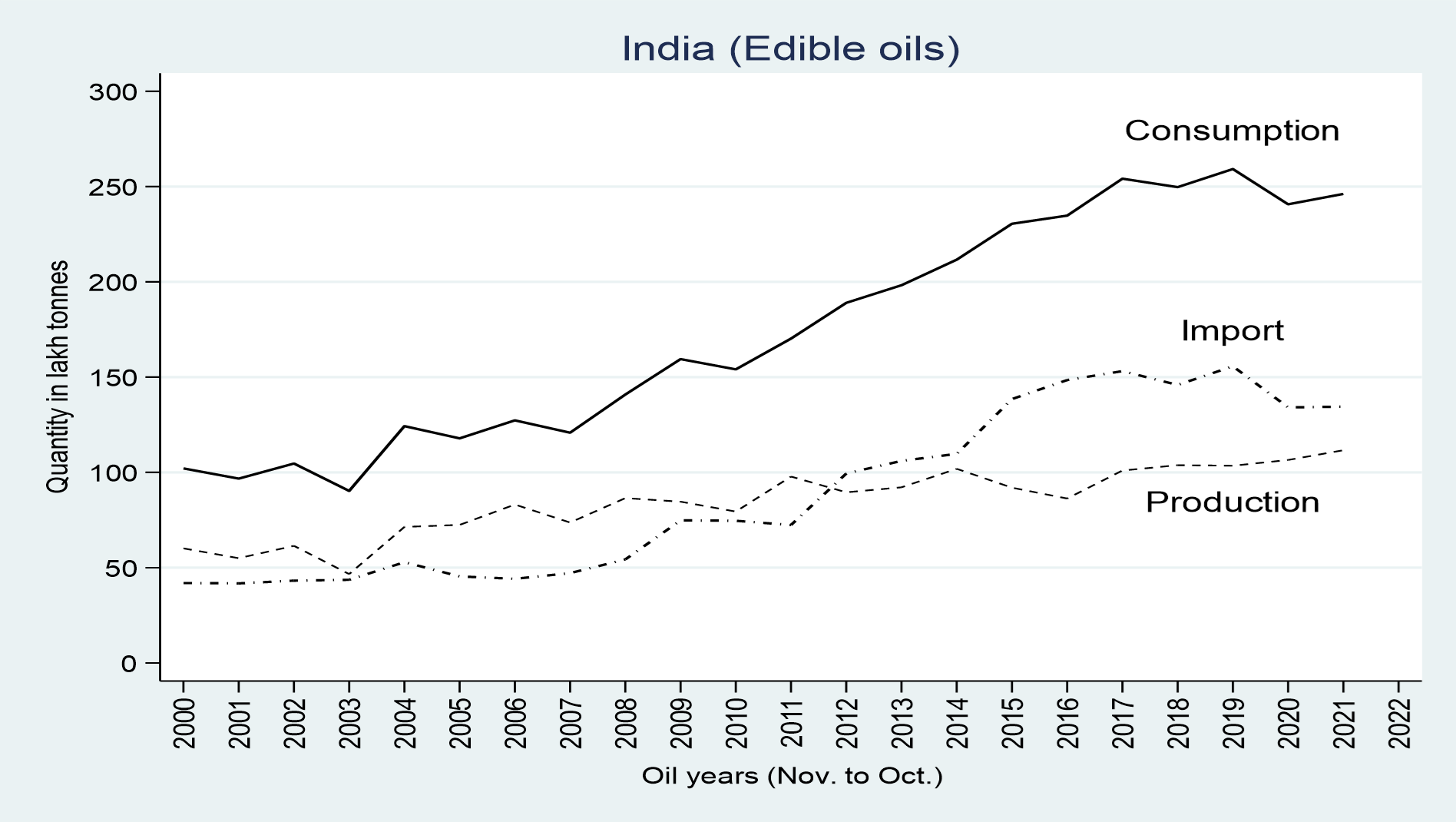

The gap between edible oil production and consumption has widened in India over the last 20 years, leading to rising and unsustainable imports. In 2022, imports accounted for around 60% of domestic vegetable oil consumption and required a whopping USD 19 billion (INR 1,570 billion) of foreign exchange reserves.

Imports have surged to catch up with consumption of vegetable oils in India.

Source: FAOSTAT data

Hybridization has the potential to increase yields to levels higher than both of the parental lines of a crop, often termed ‘hybrid vigor.’ However, for self-pollinating crops like mustard, the conventional plant breeding process can be unstable under some climatic conditions, leading to yield penalties. GM technology circumvents these challenges and provides an effective hybridization mechanism that is stable under a wide variety of conditions.

The superiority and convenience of this technology found quick applications across countries and was successfully incorporated for rapeseed development in Canada (1996), the US (1999), and Australia (2008). Mustard breeders at the University of Delhi took recourse to GM technology and developed the first GM hybrid, DMH-11, in 2002, employing the PGS method with some modifications.

Yield gains and safety for food and the environment

Field trials for testing the yield advantage compared to the national check varieties of DMH-11 showed gains of 37% over the national check variety. The GM mustard hybrid also yielded higher than both the parental lines, Varuna bn3.6 and EH-2 modbs2.99.

For more than 20 years, the multilayered and structured regulatory system subjected GM mustard to a long list of tests for phenotypic, molecular, compositional, and food and environmental safety. After prolonged testing, the GEAC finally declared that the technology was safe for food, feed, and the environment, recommending environmental release in October 2022.

The cost of regulatory delay

The financial losses to the farming community due to risk-averse policies and delays in the approval of new technologies can be substantial. Our estimates show that the cost of regulatory delays was high for transgenic DMH-11 mustard and could be USD 16 billion (124,306 crore) over the nine-year period from when the technology was fully ready in 2016 to 2024, when it might reach farmers’ fields subject to legal hurdles. Out of this, seed companies would take only 1% of the additional gains, with the remaining 99% going to the farming community. Further, production losses due to the delayed adoption amount to 15–20 million tons, which could have cooled soaring oilseed prices and food inflation to help people experiencing poverty. The additional production in 2024 would be equal to bringing an additional 3.4 million ha under mustard production.

Achieving an efficient hybrid seed production system is a one-time breakthrough. The resultant parental events of DMH-11, bn3.6 and modbs2.99, could be leveraged to produce several new hybrids, crossing recent varieties with more significant yield advantages for a turnaround in Indian mustard, replicating the success of Bt cotton. Developed by breeders at domestic and public-funded universities, DMH-11 and its parents have been declared safe for food, feed, and the environment after 20 years of tests by the robust and multilayered regulatory system. Around six million smallholder farmers growing more than 12 million hectares of mustard crop, in addition to millions of vegetable oil consumers, are likely to benefit from enhanced incomes and lower prices if GM mustard reaches farmers’ fields.

Chandra S. Nuthalapati is a visiting professor at TCI and a professor of economics at the Institute of Economic Growth in New Delhi, India.

David Zilberman is a professor and Robinson Chair in the Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics at the University of California, Berkeley.

Matin Qaim is the Schlegel Professor of Agricultural Economics and Director at the Center for Development Research (ZEF) of the University of Bonn, Germany.

Prabhu Pingali is the founding director of TCI.

Featured image: A woman walks through a mustard field in Rajasthan, India. (Photo by Abhi Verma/Shutterstock)