How Soybean FPOs Can Use Futures Contracts to Manage Risk

Price volatility affects all members of the agricultural value chain, but smallholder farmers in developing countries are particularly vulnerable to adverse prices. In general, price hedging mechanisms for smallholder farmers are limited and, in many cases, not used. With appropriate infrastructure (physical, market, and institutional), price hedging strategies that improve farmers’ livelihoods could be made available to market participants.

Some agricultural regions in India have the potential to facilitate the creation of price-hedging mechanisms for the benefit of the agricultural value chain. This blog describes our experience and observations on the available infrastructure for price hedging among soybean growers in Latur, India.

In a previous blog post, we described the soybean value chain and infrastructure available for farmers in Latur. The value chain for soybeans, as well as other crops, is well-developed in this area. Many FPOs in the region have the infrastructure to receive, store, dry, clean, and bag crops; buyers, including oilseed processors, are abundant; and services, such as risk-consulting firms and financial institutions that offer collateralized credit based on warehouses receipts, are common. Some local farmer producer organizations (FPOs) use state and international institutions grants to build post-harvest processing facilities, including warehouses. In short, the available infrastructure of the soybean value chain is favorable to producers and their FPOs.

The warehousing system as part of the value chain in Latur

Warehousing plays an important role in risk management in agriculture. Storage allows temporal diversification of crop sales, preventing distress sales at harvest, when supply is more abundant. Under certain conditions (competitive market, annual harvest, and a storable crop) the crop price is lowest at harvest and increases over time by the marginal cost of storage. Changes in demand also influence crop prices. Price differences across time provide market signals for efficient allocation of the supply over a continuous demand, aided by the warehousing system. The systematic, and predictable, variation of crop prices in a competitive market does not translate into profit opportunities, rather they reflect arbitrage costs.

Certified warehouses test incoming crops for quality, and receipts include detailed information on the produce being stored, such as humidity level and percentage of foreign matter. (Photo by Leslie Verteramo Chiu/TCI)

Some professionally managed warehouses can provide warehouse receipts for producers. Generally, these warehouses are certified by the government or by the futures commodity exchange (e.g. NCDEX). Warehouse receipts are certificates of ownership that can be used as collateral for farm credit. They are also tradable instruments that play a fundamental role in futures commodity markets. Only warehouses certified by the government, or the futures commodity exchange, can issue receipts that are accepted as tradable instruments by institutions. Transfer of receipt ownership is simple but requires notifying the warehouse and endorsing the receipt to the new owner. The FPO warehouses that we visited in Latur were not certified and thus cannot issue receipts.

Certified warehouses have strict management, security and safety controls, and their own laboratory for testing the quality of incoming crops, guaranteeing produce integrity. Warehouse receipts include detailed information on the factors of the produce being stored that affect its price, such as humidity level, percentage of foreign matter, and size and appearance of the grain/produce. Commodity market prices imply a certain expected quality level of the produce. In other words, the price reflects a standard quality of the produce. Differences in quality from the expected market baseline result in a premium or discount over the market price.

In all of the warehouses that we visited, the produce needs to be stored in jute bags—generally 50kg bags—for ease of sampling. Warehouse fees are paid before withdrawing the produce, and are generally quoted in the weight of produce stored per time period (e.g. ton/month).

The futures commodity market’s link to the warehousing system

NCDEX, a futures commodity market, plays another important role in the agricultural value chain in the region, complementing the local warehousing system. A futures commodity market provides the infrastructure where standardized commodity contracts are traded for future delivery. The two parties in a commodity futures contract are generally a producer, that sells a futures contract, and a processor, that buys the contract. Futures contracts specify a delivery date, produce quality, and the premium or discount from the market price resulting from any quality variation. Futures contracts also specify delivery points for the produce taken by the contract seller.

Postdoctoral Research Fellow Pallavi Rajkhowa takes notes during a visit to a soybean warehouse in Latur, India. (Photo by Leslie Verteramo Chiu/TCI)

The contract prices reflect the delivery of the produce to a delivery point. These delivery points are certified warehouses. Latur, being an important soybean production region, has an NCDEX-certified warehouse. When delivery of the produce takes place, the warehouse issues a receipt to a contract buyer.

Futures contract sellers can avoid delivery if they offset their futures position by buying a similar contract before the delivery date. The warehousing system in Latur allows futures market participants to hedge their position more effectively, develop a marketing strategy, and seek arbitrage opportunities (if any).

Futures commodity markets can incentivize the use of warehousing facilities through futures price dissemination. When warehouse fees are known (which is the case), as well as futures contract prices, a producer can lock in the price for future delivery (e.g. 6 months after harvest) by selling a futures contract and storing the crop in certified warehouses. When the futures contract expires, the seller can transfer ownership and pay the warehousing fees and receive the contract price for its produce. Under this strategy, the seller knows the warehouse costs and selling price at delivery, eliminating price risk in the contract.

What role can the futures derivatives market play in managing price risk?

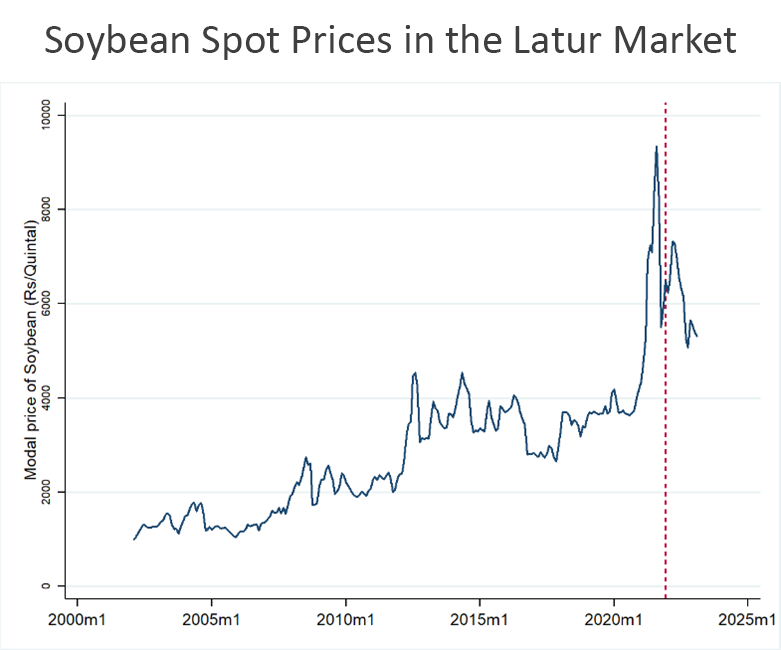

Through our conversations with various stakeholders in the soybean value chain, we also wanted to understand the issues of volatility in soybean prices and the potential role of the derivatives market in reducing some of these risks. As shown in the chart below, soybean prices are quite volatile in the Latur market.

Price volatility in Latur has several causes. First, soybean is a rainfed crop and its production is highly dependent on weather conditions. Erratic rainfall or droughts can lead to lower yields and higher prices, while favorable weather conditions can result in higher yields and lower prices. Second, the price of soybeans in India is affected by global market trends, especially in countries such as Brazil, the US, and Argentina, which are the largest soybean-producing countries in the world. Any changes in their production, demand, or trade policies can affect prices in India. Third, government policies such as the imposition of limits to stockpiles and sudden changes in import/export policies can affect domestic prices. Fourth, the demand for soybean in India is mainly driven by the livestock feed and food processing industries. Thus, any changes in the demand or supply of soybeans can lead to price volatility.

Note: On December 20, 2021, SEBI suspended futures and options trading in agricultural commodities such as chana, mustard seed, crude palm oil, moong, paddy (Basmati), wheat, and soybean.

Source: Agmarknet and NCDEX

As we discussed in our previous blog post, the FPO board members that we interacted with in Latur had the experience of trading in the futures market before it was banned in 2021 after a rapid rise in prices. These FPO members feel that the derivatives market has the potential to deal with the volatility in soybean prices that they often experience. Futures markets allow farmers to lock in prices for their soybean harvest by selling futures contracts during sowing. This enables them to protect themselves against an unanticipated drop in prices due to erratic weather conditions that may affect the soybean supply. If spot prices fall at the time of delivery, the FPO’s futures contract becomes valuable, which will allow them to offset the losses incurred from lower prices in the spot market.

The FPO members also said that futures markets provide a transparent price discovery mechanism that reflects the current supply and demand dynamics of soybeans. The market price in the futures market can serve as a reference for FPOs to determine the fair value of soybeans, which can help them make better decisions about planting, selling, or storing their crops.

We also spoke with the board members about the potential of using options as an alternative method for hedging price risk. A put option guarantees the producer the right to sell a futures contract at a certain price (strike price) and a specified date (expiration). The producer can exercise the option only if the market price falls below the strike price at expiration. The FPO members we spoke with felt that options could be a viable possibility to serve as price insurance for both producers and traders who face price volatility.

Futures contracts are underutilized by FPOs

Market mechanisms to hedge against agricultural price volatility can be implemented through the use of futures contracts supported by a network of accredited warehouses. Latur has a well-established soybean value chain with modern and functional FPO infrastructure. The same infrastructure can benefit producers of other crops as well. Some of the FPOs that we visited are exploring the use of futures contracts as part of their risk management operations and are open to new price hedging mechanisms (e.g. option contracts). The warehousing system plays a key role in the operation of the futures contracts market and provides an important risk management service to farmers and FPOs.

Despite the infrastructure available in Latur, smallholder farmers do not engage directly in futures contracts, and the volume of contracts traded in futures markets, by FPOs, is very small. Further research is needed to understand the reasons why futures contracts and accredited warehousing are not being widely used by FPOs and farmers and propose solutions for price hedging uptake.

Leslie Verteramo Chiu is a research economist at the Tata-Cornell Institute.

Pallavi Rajkhowa is a postdoctoral research fellow at the Tata-Cornell Institute Center of Excellence in New Delhi, India.

Featured image: Soybeans are stored in jute sacks in a warehouse in Latur, India. (Photo by Leslie Verteramo Chiu/TCI)