TCI Partners with PRADAN to Improve Agricultural Climate Resiliency in India

Rice is perhaps the most important crop grown in India, where it accounts for roughly a third of all cultivated land. But the relatively high greenhouse gas emissions associated with rice production contribute significantly to climate change, while the disproportionate share of starchy rice in Indian diets increases the risk of non-communicable diseases. Moving away from rice production and increasing the cultivation of more nutritious, climate-friendly crops could help address both issues.

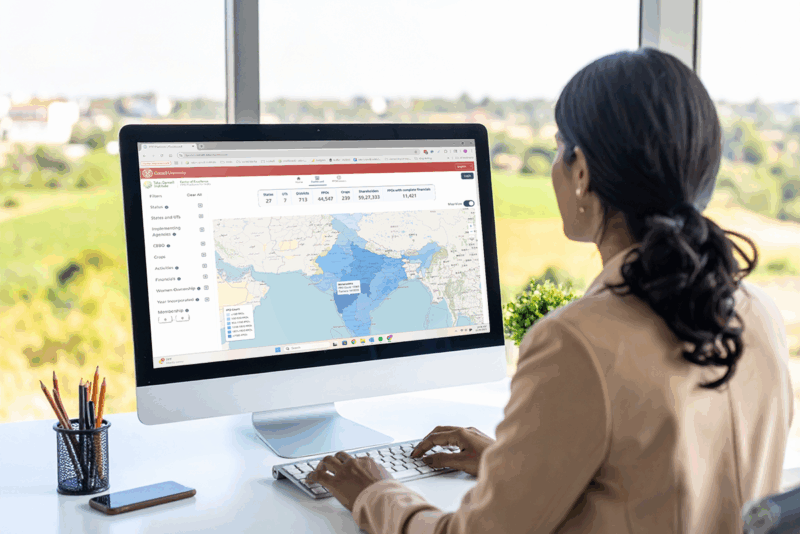

The Tata-Cornell Institute for Agriculture and Nutrition (TCI) is partnering with Professional Assistance For Development Action (PRADAN) on a project that aims to illuminate pathways to diversify agriculture in the state of Chhattisgarh away from rice in order to improve climate resiliency, increase farm income, and encourage healthy dietary practices.

“Taking steps to reduce the net greenhouse gas emissions of agricultural systems and make them more resilient to the effects of climate change is crucial to both ensuring food security and mitigating global temperature increases,” TCI Director Prabhu Pingali said. “We are happy to partner with PRADAN on this ambitious project, which will produce much-needed evidence on pathways for achieving climate-smart agriculture in smallholder systems.”

The TCI-PRADAN project, Transformation of the Agriculture System for Climate Resilience, will explore pathways to promote the diversification of Chhattisgarh’s agricultural system away from rice and towards pulses, oilseeds, and millets, which are more agro-climatically suited to the state. While systemic barriers to diversification are generally understood, the triggers and policies that could catalyze large-scale adoption are not as well known. The evidence created by the project can be used to create tools and policies supporting a shift to a more diversified agricultural system.

“Taking steps to reduce the net greenhouse gas emissions of agricultural systems and make them more resilient to the effects of climate change is crucial to both ensuring food security and mitigating global temperature increases,” TCI Director Prabhu Pingali said.

A key part of the project is the inclusion of women, who play a central role in Indian agriculture. Women’s self-help groups, collectives, and farmer producer organizations will be recruited into the project to support the shift to diversified cropping systems.

“This collaborative initiative with TCI and the Government of Chhattisgarh will create the desired models for reduction of greenhouse emission from paddy-based agricultural practices,” PRADAN Executive Director Saroj Kumar Mahapatra said. “Not only in Chhattisgarh, but we are hopeful that the models can help answer similar problems faced by smallholder women farmers in similar geographies as well.”

Dubbed the “rice bowl” of Central India, Chhattisgarh is an ideal location for the project, as more than 50 percent of the state’s gross cropped area is occupied by rice. Rice production has significantly increased in the past decade, while the production of pulses and oilseeds has slowed.

Rice production requires intensive use of fossil fuels, accounting for a fifth India’s greenhouse gas emissions associated with agriculture. By comparison, crops like pulses, oilseeds, and millets have much smaller carbon footprints. They also require less water, support soil health, and offer more affordable sources of protein and micronutrients to consumers.

The project reinforces TCI’s commitment to research aimed at ensuring that future food systems are environmentally sustainable. In 2021, the Institute began a two-year project—Zero-Hunger, Zero-Carbon Food Systems—that will develop a menu of policy options for reducing agricultural emissions in Bihar while maintaining or improving productivity.

Feature image: A farmer balances a bowl of millet on her head. (Photo by googlestock/Shutterstock)