Soybean Value Chains and Market Efficiency: Lessons from a Field Visit to FPOs in Latur

In a recent visit to Latur, a district in Maharashtra, India, we gained an understanding of the marketing channels and infrastructure available for local soybean producers. In India, Latur is a significant agricultural hub for soybean cultivation, with the second-highest acreage dedicated to soybean production after Ujjain in Madhya Pradesh. Soybean cultivation accounts for approximately 55% of the total area under cultivation in the district, making it a crucial source of livelihood for farmers. Most of the farmers in this district are smallholders or marginal farmers, with around 78% of agricultural landholdings comprising less than 2 hectares of land.

Some of the major challenges faced by soybean farmers in this region are erratic weather patterns; lack of access to timely and reliable market information; temporal volatility of prices; poor access to financial services and post-harvest infrastructure; and a lack of awareness and access to new farming technologies.

Through interactions with farmers and board members of farmer producer organizations (FPOs), we came to understand the role of FPOs in overcoming some of these challenges. We also interviewed solvent processing units, warehouse managers, and officials from the National Commodity and Derivatives Exchange Limited (NCDEX) to learn about the challenges faced by farmers and traders due to price volatility and the role warehouses and derivative markets play in managing price risks.

The importance of soybeans in India

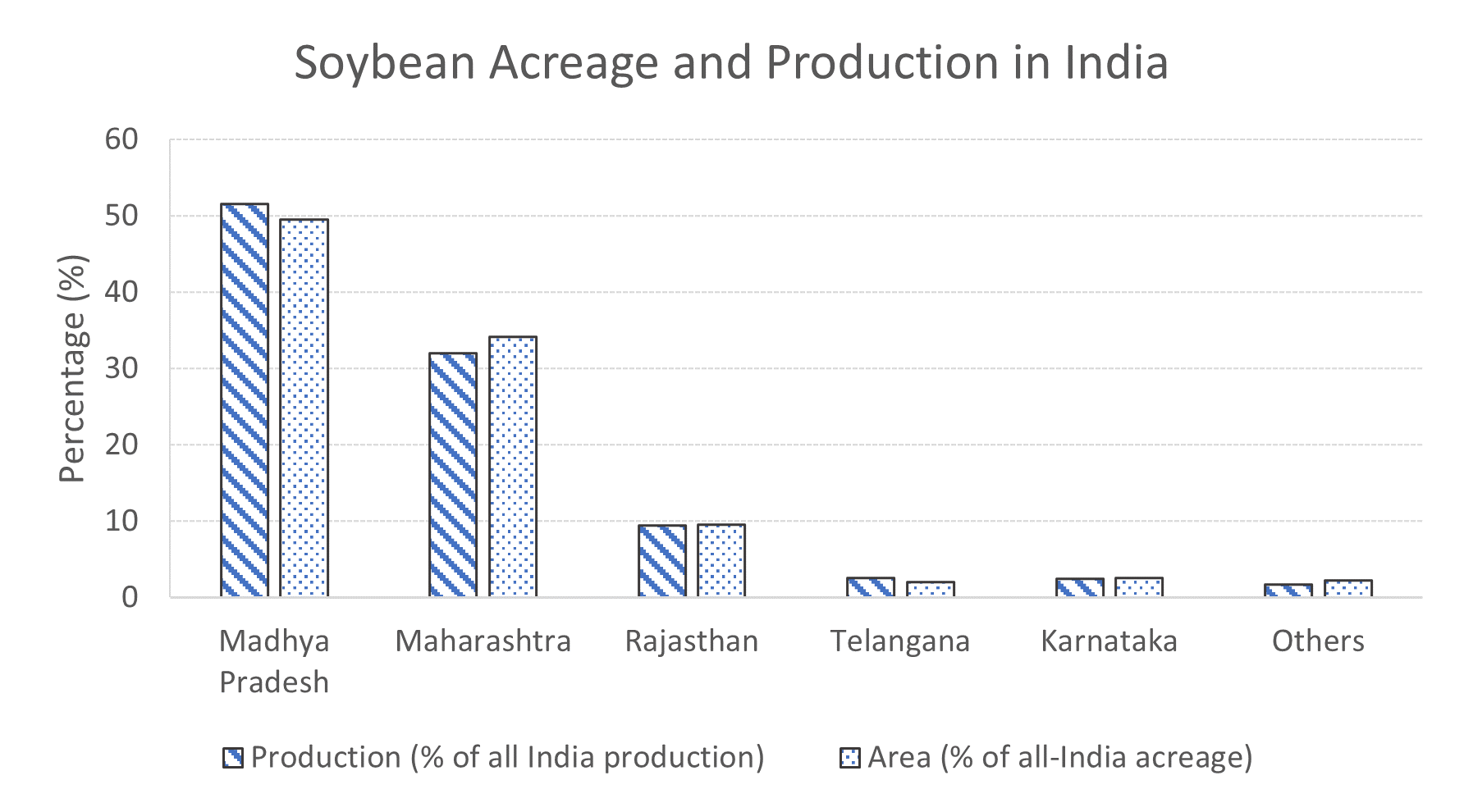

Soybean provides the largest supply of protein feed and the second-largest supply of vegetable oil worldwide. India is the fifth-largest producer and the sixth-largest consumer of soybeans in the world.

Most of India’s soybean production is consumed domestically, and a relatively small quantity is exported. The state of Madhya Pradesh is the largest producer of soybeans in India, contributing about 52% of total national production, followed by Maharashtra with about 30%. Soybean is the largest oilseed crop produced and provides livelihood to millions of farmers, generating employment opportunities along its value chain (harvesting, processing, and marketing).

*Note: Figure presents the average of three years (2015 to 2017)

Source: ICRISAT-TCI District-Level Database for Indian Agriculture and Allied Sectors

Soybeans are an important source of protein, minerals, and vitamins, especially for the vegetarian population and those who cannot afford animal protein. The consumption of soy products, such as soy milk, tofu, and soy flour, has been increasing in India, particularly in urban areas where income, and the demand for diverse foods, are higher. The oil extracted from soybeans is used in the food industry for making cooking oil, margarine, and other food products. Soybean meal, a by-product of soybean oil extraction, is a major ingredient in livestock feed.

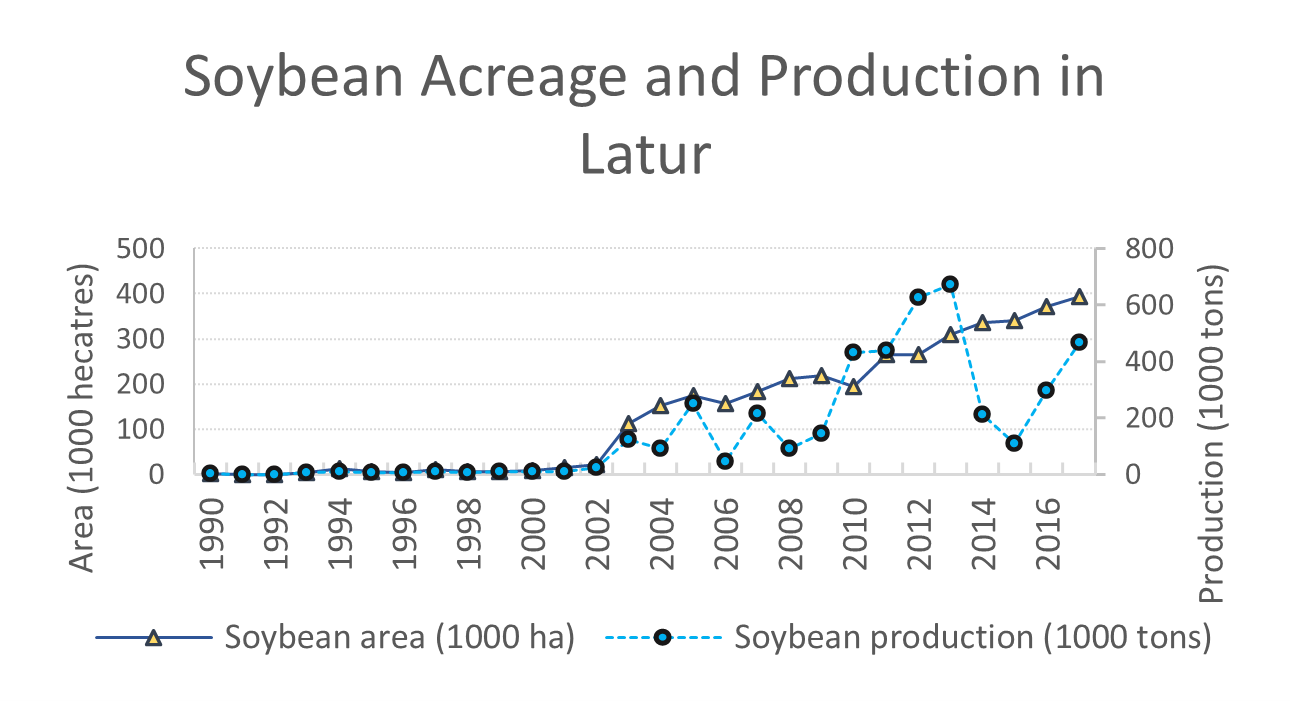

Soybean cultivation in Latur, Maharashtra

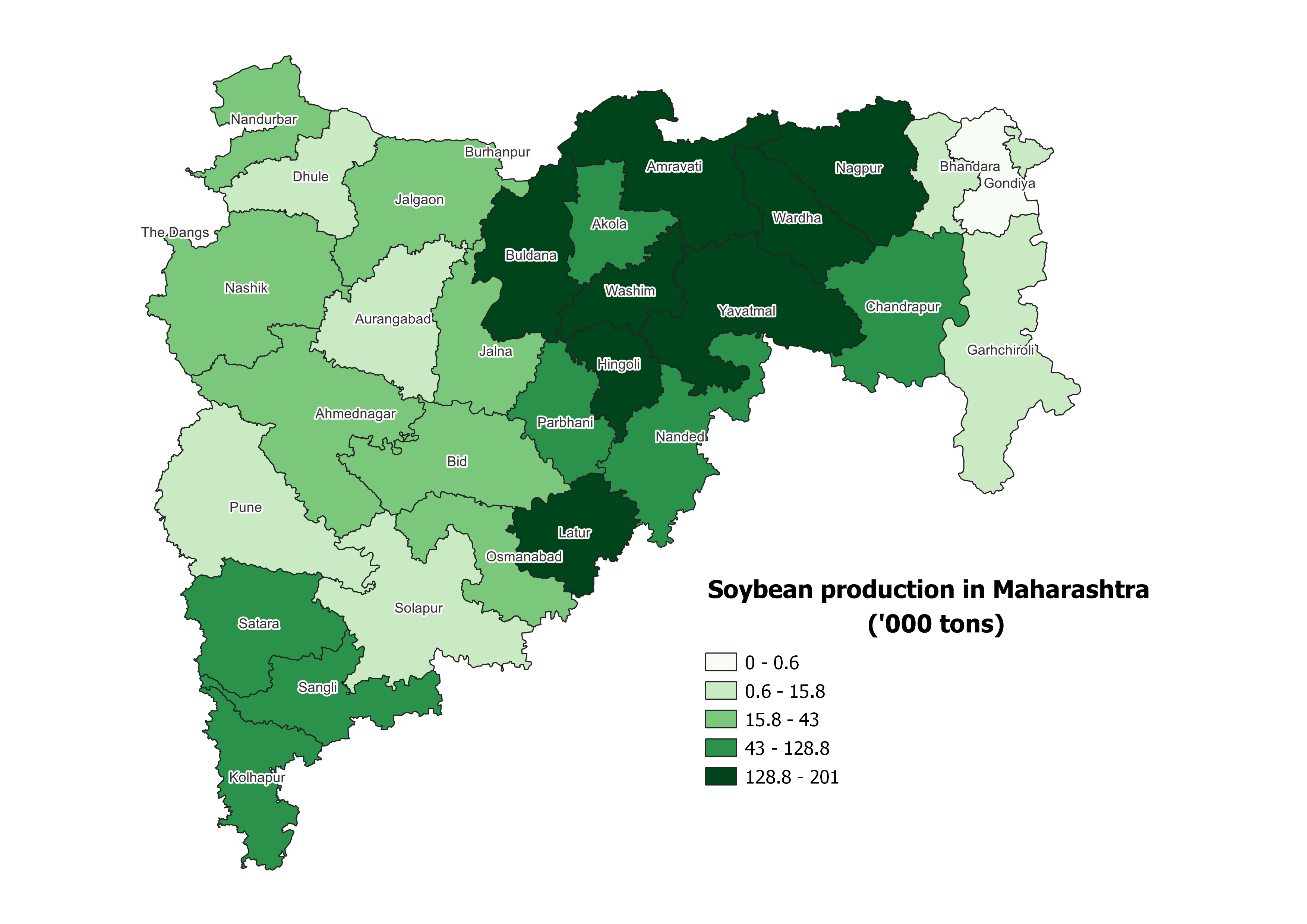

Latur is one of the largest soybean-producing districts in the state of Maharashtra and has gained recognition for its soybean farming and processing facilities. Latur has also been recognized for its well-established soybean (and other crops) value chain, which includes farmers, FPOs, traders, warehouses, market advisors, credit providers, and processing units.

Soybean cultivation typically takes place in rain-fed areas during the Kharif, or wet season, with sowing starting in mid-June or July and harvesting taking place in September. October and November are the peak soybean arrival months.

Note: Figure presents the average of three years (2015 to 2017)

Source: Map created using data from the ICRISAT-TCI District-Level Database for Indian Agriculture and Allied Sectors

Until the late 1990s, soybean cultivation was almost non-existent in Latur. However, the entry of Archer Daniels Midland (ADM), a multinational corporation engaged in food processing and commodities trading, in 1999-2000, has led to a substantial increase in soybean farming in the region over the last two decades. ADM has established an outreach initiative that spreads innovative technologies to small and resource-limited farmers. The program assists farmers in obtaining breeder seeds from state agricultural universities, provides backing for soil testing programs, arranges pre-sowing camps to enhance farmers’ awareness of different soybean varieties, and imparts technical expertise on pest control and good agricultural practices through social media. ADM also disseminates price information through WhatsApp groups and their internal call center. The entry of ADM also led to the establishment of other solvent processing units in the region. Currently, Latur has about 20 solvent processing units, making the regional soybean market very competitive and integrated.

For the past 20 years, due to consistent and fully incorporated marketing systems, a uniform cropping pattern has emerged in the region. Soybeans are grown during the monsoon season (Kharif season), while chickpea is cultivated in the dry season (Rabi season).

In recent years, due to soil infertility and the introduction of new solvent processing facilities for safflowers, there are indications of a shift away from chickpea cultivation towards safflower cultivation during the Rabi season.

Sugarcane is another important crop in the region, with higher expected returns per acre, but its production demands more water than oilseeds and other crops. The existence of ten sugar mills in the district provides incentives to grow sugarcane for those farmers with access to irrigation.

Alternative marketing channels for soybean

In Latur, we observed several distinct categories of marketing channels for soybean farmers:

Local traders and Agricultural Produce Marketing Committees (APMCs)

Small-scale farmers who face relatively high transaction costs, or need access to trader financing, tend to sell their produce to local traders operating within their village or to wholesalers in the APMC.

FPOs

Farmers who live in the vicinity of registered FPOs with warehousing facilities can sell their produce to those FPOs, who in turn sell the produce to traders and wholesalers, or directly to solvent processing units.

Two of the FPOs we visited utilized the benefits of the State of Maharashtra’s Agribusiness and Rural Transformation (SMART) project, funded by the World Bank, to construct post-harvest facilities: warehousing, drying, cleaning, and packing machines. These two FPOs have set up warehouses with a storage capacity of 2,200 MT, a cleaning facility capable of cleaning four tons per hour, and a weighing facility with a 60 MT capacity, all financed via SMART projects.

While the facilities are the assets of the FPO, procurement of soybeans is not limited to FPO members. Non-members can sell their produce to these FPOs. The FPO offers the same price to both members and non-members. FPO members receive a discount, compared to non-members, in the FPO’s input store, if available. Thus, the benefits of the post-harvest infrastructure are being shared by the community at large. Once soybeans are harvested, farmers in the vicinity have choices of where to sell their produce. Interaction with farmers suggests that prices given by the FPOs are usually higher than the prices given by traders in the local market (APMC).

The FPOs we visited also procure chickpeas and pigeon peas at the government-specified minimum support prices (MSP) on behalf of the National Agricultural Cooperative Marketing Federation of India Ltd. (NAFED). FPOs offer farmers a way to hold their crops for an extended period and provide them with an assured buyer, providing farmers with marketing options that improve their welfare. By storing soybean, farmers and FPOs operating on farmers’ behalf can engage in temporal arbitrage by waiting for the market price to improve before selling their product, reducing their dependence on distress sales. Farmers are also in a better position to negotiate with buyers and secure higher prices for their crops. Grading, sorting, and packaging facilities help farmers improve the quality of their produce, which in turn can result in higher price realization.

State and privately owned warehouses

Medium and large farmers or traders who can afford transportation also use state- and privately-owned warehouses as a marketing tool to engage in temporal arbitrage. Some warehouses in Latur are certified by the government or the futures exchange (NCDEX). These certified warehouses provide receipts that are effectively tradable instruments. Farmers and traders can also avail themselves of financing through warehouse receipts.

We visited two such warehouses in Latur: Shree Shubham Logistics Ltd., which is accredited by National Commodity Clearing Limited (NCCL); and the Maharashtra State Warehousing Corporation (MSWC). Warehouses accredited by the NCCL are used as delivery points for future contracts, in this case NCDEX. This means that futures contracts are priced for delivery to those accredited warehouses.

Once the soybean reaches the warehouse, the consignment undergoes inspection for quality and quantity. Several parameters, such as moisture content, foreign matters, and damaged beans are evaluated. The sampling methodology differs by the warehouse. Once the quality check is complete, the results of the inspection are recorded in a register maintained by the warehouse. Based on this information, warehouse receipts are generated for the stored goods. The warehouse receipt typically contains details such as the name and address of the owner of the good, the location of the warehouse, the quantity and quality of the goods stored, the valuation of the goods stored, and the date of storage.

Warehouse receipts become proof of ownership, which can be transferred, and can be used as loan collateral. The MSWC warehouse in Latur has also introduced Blockchain technology to increase transparency and improve efficiency in availing financing. Thus, these warehouses not only enable sellers of soybean to engage in temporal price arbitrage but also enable them to access formal financing.

We also interacted with an FPO that did not have warehousing facilities. This FPO used the state or private warehousing facilities to store its produce and used the warehouse receipt system to avail financing for the benefit of its members.

Direct sales to solvent-processing companies

FPOs and medium to large farmers who can afford transportation can engage in direct selling to buyers such as processors and traders who engage in bulk soybean purchases. Every morning, the 20 processing units and other buyers send their price quotes through text messages to their registered sellers, which enables farmers to decide where to send their produce.

Sale to the government under the minimum support price (MSP) program

Farmers can also sell their soybean produce to the government under the minimum support price (MSP) program. The Government of India announces the MSP for soybeans before planting season begins. This is the minimum price at which the government is willing to purchase soybeans from the farmer. However, since the market price is usually higher than the MSP, the government is not procuring soybeans. The MSP acts as a floor price.

Sale through the electronic marketplace

Farmers also have the option of selling their products through a few online platforms. One such example is NCDEX E-Markets Ltd., which allows farmers and traders to sell soybeans online in the spot market.

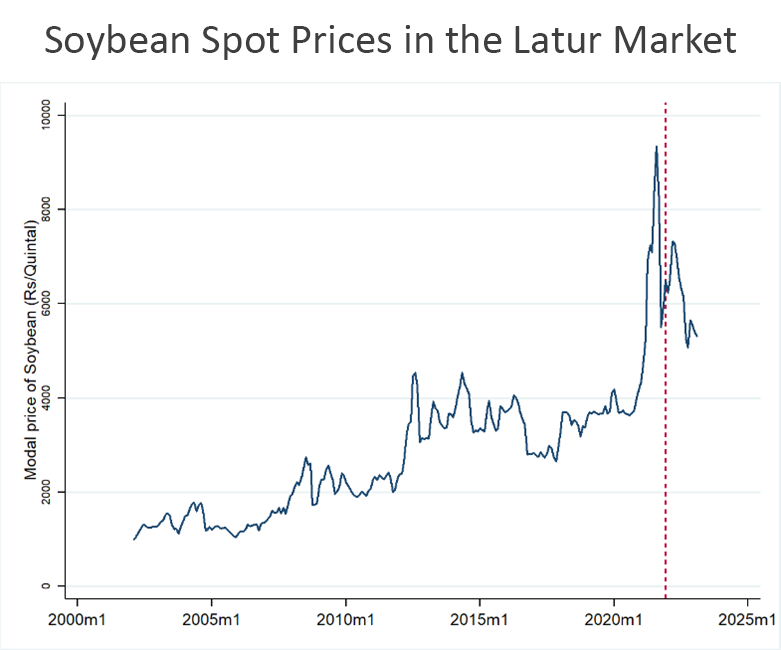

Sellers of soybeans formerly had the option of engaging in the derivatives market to hedge their price risk. During our field visit, we interacted with three FPOs that had transacted in the futures market. This allowed them to lock in prices during sowing season to hedge against any price risk. However, the Securities Exchange Board of India (SEBI) suspended futures and options trading of soybeans and other agricultural commodities on December 20, 2021, due to the rapid price increase experienced by many crops in the previous year. Initially, the ban was for one year. However, it has not yet been lifted.

Note: On December 20, 2021, SEBI suspended futures and options trading in agricultural commodities such as chana, mustard seed, crude palm oil, moong, paddy (Basmati), wheat, and soybean.

Source: Agmarknet and NCDEX

Learning from our field visit

Soybean cultivation in Latur is highly integrated, with several marketing channels available to farmers. The existence of FPOs, public and private warehouses, institutional buyers such as solvent processing units, and large exporters have made the soybean market competitive at the buyers’ end and therefore has enabled farmers to realize better prices.

Soybean farmers still face price volatility due to reasons like weather conditions, demand-supply dynamics, global trends, and government policies. A few ways to hedge the price risk are by deferring sales to a time when the market price is better and the use of institutional risk-hedging instruments such as futures and options.

The existence of several warehouses has enabled farmers and traders in this region to hold their produce and negotiate better prices. Warehouses have also enabled farmers to avail themselves of formal financing at a lower cost. Without the FPOs, small farmers would lack the access to warehouses that larger farmers have. Moreover, up to 2021, farmers also had an additional channel to hedge their price risks by engaging in the futures market. However, the ban on agricultural commodities in the futures market has removed this alternative mechanism for hedging price risks. A consistent and stable policy framework in the futures market can play a crucial role in providing smallholder farmers with better access to market information and enabling them to make informed decisions about the production and marketing of their crops.

Pallavi Rajkhowa is a postdoctoral research fellow at the Tata-Cornell Institute Center of Excellence in New Delhi, India.

Leslie Verteramo Chiu is a research economist at the Tata-Cornell Institute.

Featured image: An FPO soybean warehouse in Latur, Maharashtra, India. (Photo by Leslie Verteramo Chiu/TCI)