Improving Livelihoods Through Enhanced Goat Breeding

Goat rearing holds significant promise for smallholder farmers in India, offering resilience and income generation even during crop failure. However, reliance on natural breeding practices limits productivity due to issues like inbreeding and disease transmission. Artificial insemination presents a viable solution to enhance goat productivity by providing access to superior genetic material and desirable traits. Despite the success of artificial insemination in large ruminants, its adoption in goats remains limited due to the perception that its cost outweighs its economic benefits, compounded by underdeveloped markets for goat products.

An ongoing Tata-Cornell Institute (TCI) study aims to address this gap by providing artificial insemination and healthcare services to smallholder farmers, with the potential to improve kidding rates and the birth weights of newborn goats. By assessing the benefits and factors influencing adoption, this study seeks to promote more effective and sustainable goat breeding practices, ultimately benefiting the livelihoods of marginalized farmers.

Study setting

The study spans four Indian states: Rajasthan, Bihar, Maharashtra, and Odisha. Each state hosts a significant goat population and showcases distinct breed characteristics.

The predominant goat breeds in these states and our study villages include Black Bengal in Bihar, Ganjam in Odisha, Osmanabad in Maharashtra, and Sirohi in Rajasthan.

Breed traits

|

State |

Goat breed type |

Birth body weight (kg) |

Breed utility

|

Milk Yield/Lactation (kg) |

|

Bihar |

Black Bengal |

Male: 1.5 |

Meat, Hide |

144 |

|

Female: 1.4 |

||||

|

Odisha |

Ganjam |

Male: 2.36 |

Meat, Milk |

65 |

|

Female: 2.06 |

||||

|

Maharashtra |

Osmanabadi |

Male: 2.1 |

Meat |

40.75 |

|

Female: 1.7 |

||||

|

Rajasthan |

Sirohi |

Male: 2.29 |

Meat, Milk |

81.5 |

|

Female: 2.22 |

(Source: Kiran Kashyap, 2020)

Approximately 80% of goats are reared under the “extensive” system in India, with goats confined under housing and stall-fed. It is characterized by minimal resource input and low productivity. Breeding bucks—typically non-descript varieties—are often chosen from existing flocks and are utilized extensively for extended periods. Housing conditions are often inadequate, leading to overcrowding and heightened disease incidence, with mortality rates ranging from 20%–60%. Additionally, the marketing of goats is unorganized and relies heavily on local traders, with prices determined by visual assessment rather than live body weight. All four study states adhere predominantly to the extensive system of goat rearing.

Goat breeding practices vary across regions. In Bihar and Odisha, farmers rely on local and community bucks, while in Rajasthan, many farmers either own or hire breeding bucks. Maharashtra sees a mix of both ownership and hiring. Government programs supporting economically disadvantaged livestock owners include the provision of subsidized female goats and breeding bucks to families. These programs often focus on natural breeding and recommend rotation of bucks across households. However, this does not always happen, so the risk of inbreeding and disease transmission still holds.

Baseline survey and awareness campaign

In this context, to overcome the issues associated with natural breeding, we introduced artificial insemination with the aim of enhancing goat productivity in around 800 households across Rajasthan, Bihar, Maharashtra, and Odisha. We are implementing this program in collaboration with the BAIF Development Research Foundation, an India based organization dedicated to improving rural livelihoods.

At the start of the study, a baseline survey was conducted with one respondent from each household, typically the individual primarily responsible for goat rearing. The survey encompassed the socio-economic characteristics of the households, goat-rearing practices, details about the sale of goats and related products, access to goat health services, breeding methods, and information about the goats’ offspring, among other information.

Following the baseline survey, an extensive awareness campaign was conducted targeting all sampled households, with a focus on explaining the benefits of various interventions. Participants were informed about the advantages of artificial insemination, including the enhanced genetic quality of progeny, reduced risk of sexually transmitted diseases, and increased kidding rates. Additionally, they were educated on the benefits of deworming to combat parasitic infections and improve goat health, as well as the importance of vaccination to confer immunity against infectious diseases.

Participants were given the choice to join either the intervention or control group, with all households receiving essential services such as deworming, vaccination, castration, and access to goat health services. Those opting for the intervention arm would receive additional services related to artificial insemination, all provided free of cost, with ongoing monitoring of goats and progeny until the endline survey.

|

Variables |

All |

Bihar |

Odisha |

Maharashtra |

Rajasthan |

|

Households |

795 |

221 |

200 |

180 |

194 |

|

Intervention |

621 |

202 |

172 |

73 |

174 |

|

Control |

174 |

19 |

28 |

107 |

20 |

Across all states, 621 households opted for the intervention.

Outcomes and preliminary results

Our study aims to explore various facets of the impact of artificial insemination for goat rearing. First, we aim to understand farmers’ perceptions of the benefits of artificial insemination.

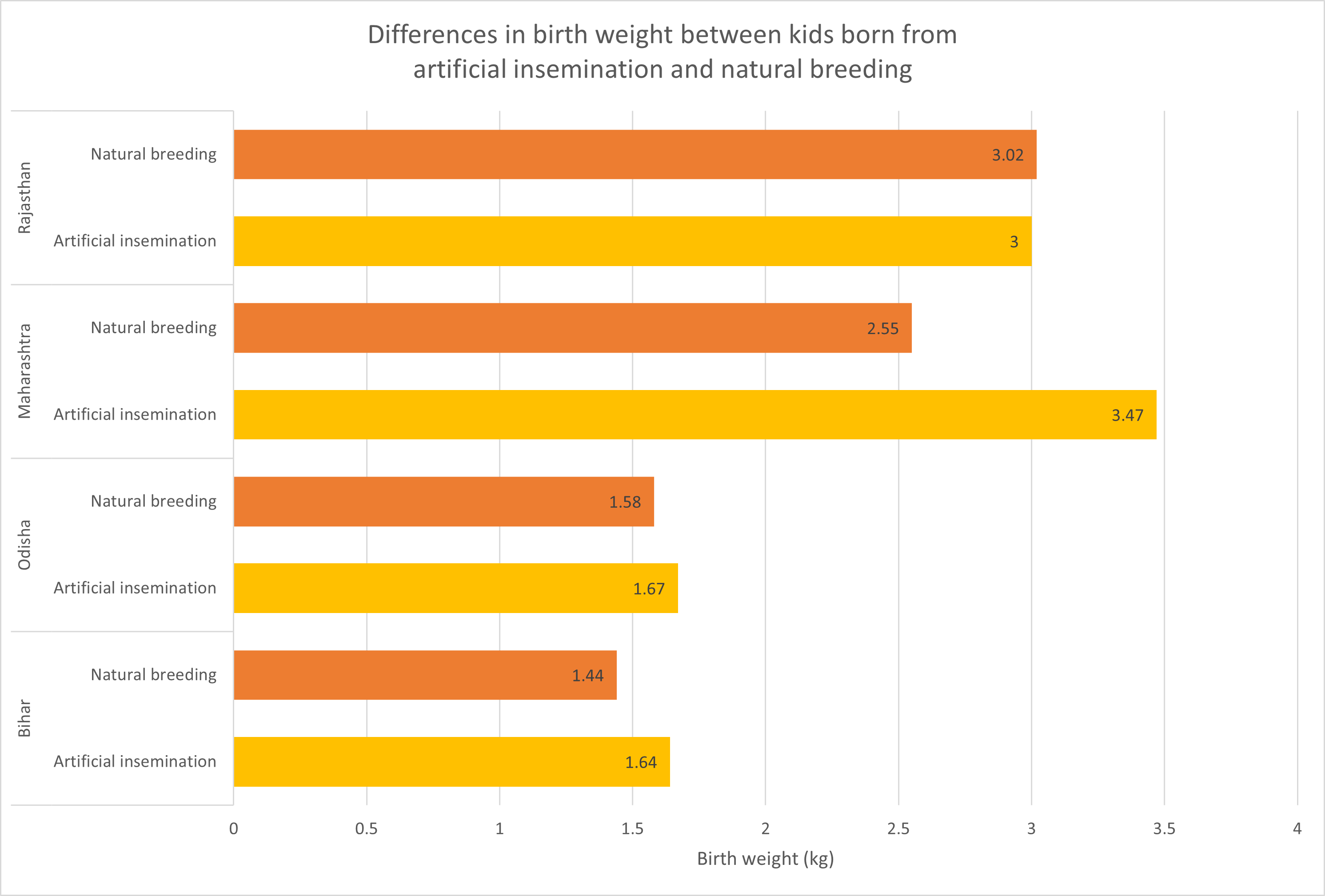

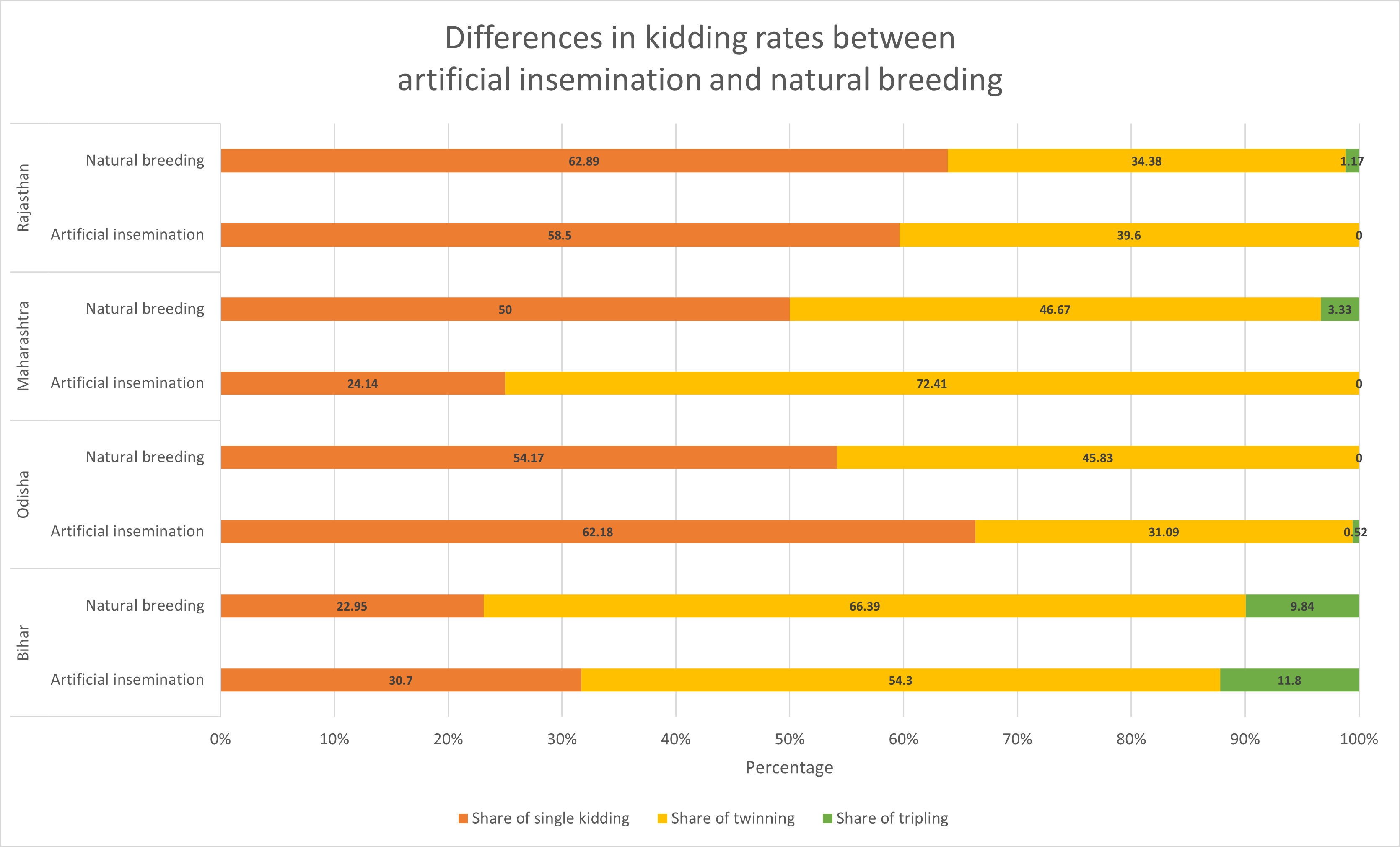

Second, we aim to corroborate these perceptions with tangible evidence by examining actual improvements in the goat-rearing system, as demonstrated by differences in birth outcomes between offspring conceived naturally and through artificial insemination. To do so, we use data collected from study households on the goat progenies’ birth weight and kidding rate (i.e. the number of kids born in one birth).

Third, we want to ascertain farmers’ willingness to pay for artificial insemination.

Using data collected from September 2023 to February 2024, we have some preliminary findings related to the impact of artificial insemination on kidding outcomes.

At the start of our study, we predicted that artificial insemination would yield higher birth weights. Our data so far suggests that artificial insemination has varying degrees of effectiveness in influencing birth weight across different regions. In Bihar and Odisha, offspring generated through artificial insemination generally exhibited slightly higher birth weights compared to naturally born offspring, with differences of 0.2 kg and 0.09 kg, respectively. In Maharashtra, the difference in birth weights is more pronounced, with artificial insemination offspring weighing, on average, 0.92 kg more than naturally born offspring. Interestingly, in Rajasthan, there is minimal disparity in birth weights, with a negligible difference of -0.02 kg.

We also posited that the kidding rates would be higher with conception through artificial insemination. We see that in Bihar, out of total artificial insemination births, 54% were twinnings, compared to 66% for natural births. We see similar results in Odisha, indicating that natural mating might be more conducive to twin births in these regions.

However, Maharashtra and Rajasthan show the opposite trend. Artificial insemination has the highest share of twinnings in Maharashtra at 72.41%, compared to 46.7% for natural breeding. In Rajasthan, the share of artificial insemination twinning is 39.6% compared to 34.4% for natural breeding. This suggests the impact of artificial insemination on kidding outcomes varies between regions.

We conducted focused group discussions in all four states and found that the perception of artificial insemination was generally positive. The participants plan to continue with artificial insemination after the study, citing time savings from the in-house delivery of services rather than roaming the village to locate a buck for breeding. No significant challenges were faced in its adoption. Further, the participants felt that the goats had better weights, improved skin tone, and healthier kids.

In the upcoming months, we will be able to present updated results for these outcomes by including data from additional kidding. When our endline survey is complete, we will also be able to present data on farmers’ perceptions of the benefits of artificial insemination and their willingness to pay for the service.

Payal Seth and Bharath Chandran C are research consultants at the TCI Center of Excellence in New Delhi. Bhaskar Mittra is the associate director of TCI.

Featured image: A young goat eats a leaf. (Photo by Maureen Valentine/TCI)