Zero Hunger in India Is Possible with Diverse Food System

With some 200 million people suffering, India has relatively high rates of hunger compared with the rest of the world. However, malnutrition is not uniform throughout the country, and its prevalence corresponds to the uneven levels of economic development between different regions.

According to a new report from the Tata-Cornell Institute for Agriculture and Nutrition (TCI) that published July 15, researchers have mapped opportunities for India to reduce hunger and improve overall nutrition by reorienting its agricultural policies in favor of more nutritious foods.

In Food, Agriculture, and Nutrition in India 2020: Leveraging Agriculture to Achieve Zero Hunger, TCI researchers assess India’s progress toward achieving zero hunger by 2030 – a sustainable development goal established by the United Nations General Assembly in 2015.

The new report assesses the prospects for enhancing productivity and increasing farm income across India, and it emphasizes the need for continued investment in agricultural infrastructure.

To provide its people with nutritious foods, India must turn the focus of its food policies from quantity to quality. Without policies that promote access to and availability of nutrient-rich foods, much of the country is left with diets high in either nutrient-poor grains or fattening processed foods.

Since the late 1960s, India has made considerable progress in reducing hunger in terms of calories, but many people remain undernourished, and now the country is also facing rising rates of obesity. The TCI report says this is due to government policies that boosted staple grains, like wheat and rice, which helped meet people’s caloric needs but are now inhibiting the production of more diverse and nutritious foods.

“To provide its people with nutritious foods, India must turn the focus of its food policies from quantity to quality,” says Prabhu Pingali, director of TCI and professor in the Charles H. Dyson School of Applied Economics and Management, with joint appointments in the Division of Nutritional Sciences and the Department of Global Development in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences (CALS). “Without policies that promote access to and availability of nutrient-rich foods, much of the country is left with diets high in either nutrient-poor grains or fattening processed foods.”

In the economically lagging and less agriculturally productive states of central and eastern India, 63% of dietary calories come from cereal grains. This leads to stunting and wasting of bodies due to nutrient deficiencies in diets, especially for the impoverished.

In contrast, in the more developed and more agriculturally productive states of northwestern and southern India, access to processed foods and edible fats have had the opposite effect. In the last 10 years, the rate of obesity doubled for men and increased by 62% for women, bringing with it a rise in diabetes and heart disease.

The Food, Agriculture, and Nutrition in India 2020 report is available for download in PDF format.

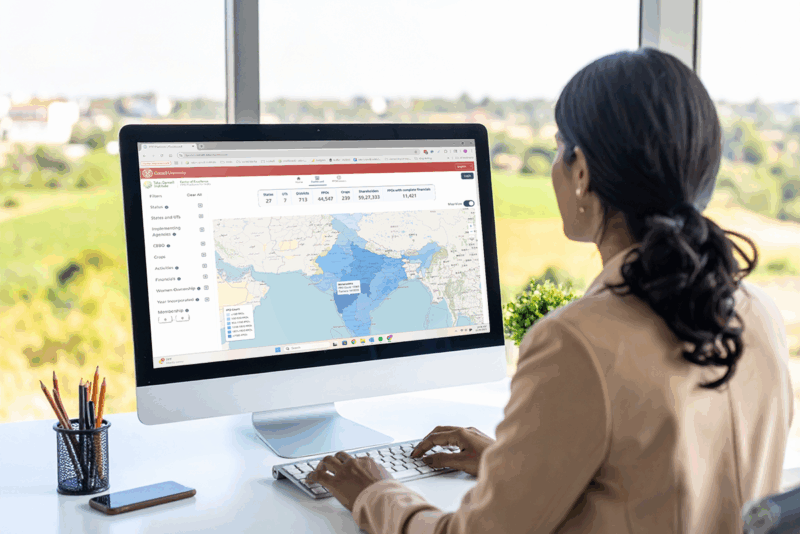

Using district-level data, the report’s authors created maps showing the dominant crops grown in different areas and offered advice for increasing productivity and diversifying local food systems.

For example, for the cropping systems of eastern India – which are less productive due to poor infrastructure and agroclimatic conditions – they recommend adopting crops that require less water, such as pulses, coarse cereals, and oilseeds.

Pingali and his team collected data for food systems and nutrition maps using the District-Level Database for Indian Agriculture and Allied Sectors, a comprehensive data platform jointly developed by the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT) and TCI, which is part of CALS and hosted by the Dyson School.

“India has many different agroecologies that lend themselves to distinct cropping systems,” says Kiera Crowley, M.S. ’17, co-author and research support specialist at TCI. “The widespread data collected by TCI and ICRISAT proved indispensable in our efforts to map those systems.”

Tailoring efforts to local cropping systems will help ensure that new policies can be as effective as possible. However, this approach requires close coordination between all levels of government. “Breaking out of our disciplinary and organizational silos is crucial for ensuring success in achieving the zero-hunger goal,” Pingali says.

Enhancing agricultural productivity is particularly important in the lagging states. As the report notes, states that failed to invest in agriculture during the Green Revolution of the 1960s were left with weak agricultural sectors and high levels of poverty.

Since the lagging states are unlikely to match the productivity of staple-grain agriculture in developed states, the researchers recommend focusing efforts on adding more diverse crops like pulses, coarse grains, fruits, and vegetables. With investment from the public and private sectors, farmers could take advantage of the growing demand for these crops, which can be sold at higher prices than staple crops.

“Investing in agriculture, especially in lagging states, can cause a chain reaction that improves nutrition,” says Andaleeb Rahman, co-author and postdoctoral associate. “It increases farmers’ income, allowing them to purchase more nutritious foods, while also improving household health environments and allocation of food within the home, both of which are key to better nutrition outcomes.”

The report is the first in a series from TCI. Each report will provide periodic assessments of the food, agriculture, and nutrition situation in India.