Small Packs With Big Impact: The Role of Consumer Packaging

This blog post is the third in a four-part series exploring the connection between food packaging and food loss and waste within sustainable food systems, focusing on nutritious, perishable foods. Throughout this series, food loss and waste will be defined as a reduction in the quantity or quality of the edible portion of food intended for human consumption when food is redirected to non-food uses or when there is a decrease in the nutritional value, food safety, or other quality aspect from the time food is ready for harvest or slaughter to consumption. Read the first and second posts in the series.

Imagine grocery shopping with just one reusable bag, leaving the store with everything you need without ever touching a single item of food. Is it possible? Absolutely. Consumer packaging makes it so. But is it desirable? That’s a more complex question that depends on a variety of factors.

As populations urbanize and incomes rise, consumers increasingly demand higher-value and convenient food. While “packaged food” often brings processed, nutrient-poor foods to mind, packaging can serve important functions for all foods: protecting it, extending shelf life, providing information and enhancing convenience.

“Wasted Potential” is available to download for free via open access.

Consumer packaging encompasses all materials used to enclose or protect food products intended for sale. This includes pre-packaged foods, where food is portioned and sealed in advance for consumer convenience. It also includes point-of-purchase packaging of bulk items, where consumers select and package the desired items and quantity themselves, often using containers (e.g., bags or boxes) provided by the retailer or brought from home (e.g., reusable produce bags).

Perishable, nutritious foods—fruits, vegetables, dairy, eggs, meat and fish—are sold both pre-packaged or loose, depending on the retailer and product. The packaging strategy for these foods is heavily influenced by the specific food value chain and target market. While certain pre-packaging methods can improve food condition and shelf life compared to no packaging, understanding the lifecycle and function of consumer food packaging for nutritious foods is essential for transitioning to sustainable food systems that support healthy diets.

Consumer packaging and food loss and waste: A complex relationship

Consumer packaging can both reduce and contribute to food loss and waste (FLW). Well-designed packaging protects food from contamination or physical damage, extends shelf-life and provides space for labels with storage and consumption information. Packaging that improves the convenience of food preparation and consumption can help ensure that purchased food is actually eaten.

However, packaging can also contribute to FLW. Point-of-purchase packaging options are often limited and may not be ideal for all produce and food types. For example, while plastic produce bags might be sufficient for durable items, like potatoes, they offer minimal protection against bruising for delicate produce, such as ripe tomatoes. Similarly, meat or fish wrapped in butcher paper may lack a proper seal, risking leaks and potential contamination of other groceries.

Pre-packaging can interfere with consumers’ ability to assess key quality attributes like smell and texture. Opaque packaging and labeling can further obscure the food’s appearance. This is particularly problematic for fresh produce, which typically have greater natural variation than processed foods, where uniformity is often the goal. Further, pre-determined quantities, whether single or multi-serving, can lead to purchasing more or less than desired, potentially impacting the extent of FLW that occurs in households.

The rise of plastic: A packaging paradox

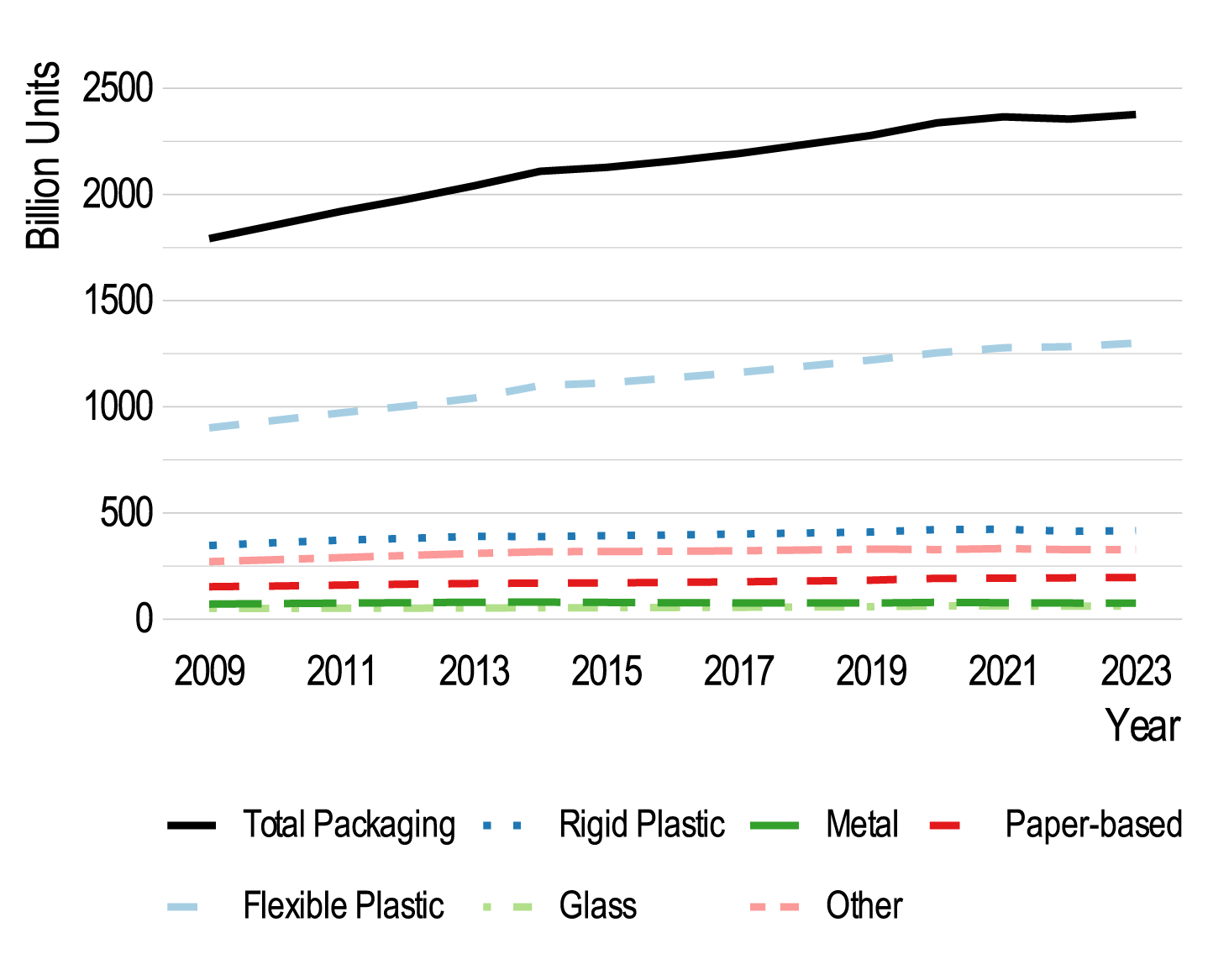

While packaging can be made from various materials (glass, metal, paper, cardboard, etc.), plastics, both rigid and flexible, have become widespread due to their relative versatility and cost-effectiveness. The rise of plastic food packaging has made it easier to package perishable foods with high moisture content without adding too much additional weight. However, the rise in the use of plastic raises concerns about the potential health and environmental impacts of plastic production, use and disposal.

Trends in global food packaging material, 2009–2023 (Wasted Potential, 2026)

The disposal of plastic packaging is particularly concerning because the benefits of its use (e.g., reduced food loss and waste) and the burden of its end-of-life impacts may be experienced in different locations and populations. While some plastic is recycled, a significant portion is exported, incinerated or landfilled. In Europe, for example, only 26.3% of post-consumer plastic was recycled internally in 2018, while 6.2% was exported. Open burning plastic waste, a common practice in some regions, not only adds to global greenhouse gas emissions, but pollutes local air quality. Analyzing the sustainability of food packaging requires a holistic view, considering local and global impacts throughout the entire lifecycle to understand who benefits and who loses.

Sustainable food packaging solutions demand a careful balancing act that must account for the diverse packaging trends of different foods that support healthy diets. For example, in Hyderabad, India, fresh produce is typically sold loose, though some supermarkets offer pre-packaged options. Even so, convenience trends may drive increased packaging of fresh produce. Online grocery platforms like Big Basket in India, for instance, often pre-pack produce in plastic containers and sealed bags to improve operational efficiency and enhance consumer convenience.

The effective packaging dilemma: Complexity brings challenges

Even with recyclable plastics, the vast majority end up in landfills, are mismanaged or are incinerated. Less than 10% is currently recycled. Mismanaged waste includes open burning, dumping into waterways and disposal in unsanitary landfills. The lack of a robust business case becomes a major challenge for plastic recycling due to limited markets for recycled materials.

Tomatoes are sold loose at a supermarket in Hyderabad. (Photo by Jocelyn Boiteau/TCI)

The diversity of plastics adds another layer of complexity. “Plastics” refer to a wide range of different materials. But, there is a lack of clarity on which plastics are recyclable or unrecyclable, which varies depending on the material and available infrastructure. What’s recyclable in one context may not be in another.

Newer packaging materials designed to extend shelf life, while beneficial for reducing FLW, can be even harder to recycle. Aseptic packaging, for example, uses multiple layers of different materials, requiring specialized recycling processes. Recycled material must also have value in other industrial processes to complete a circular economy.

Food packaging, particularly for perishable, high-moisture foods, presents unique challenges. Food residue makes cleaning and recycling difficult. Package type and design can influence the amount of food residue that remains trapped within a package.

Package size also plays a role. Larger portions may reduce packaging waste per unit of food but can lead to increased FLW if not eventually entirely consumed after opening. Smaller portions may minimize food waste but increase packaging waste.

The future of consumer packaging: A holistic approach

With a growing global population and increasing urbanization, sustainable packaging solutions are crucial for minimizing both FLW and the environmental impact of packaging. Trade-offs and solutions will vary across food systems and value chains, requiring multidimensional analyses that consider health (food safety and exposure to chemicals and plastics) and environmental impacts (local to global, from production to end-of-life).

Food packaging and sustainability must be viewed within the broader context of food systems. How might packaging change with shifts in dietary patterns? A holistic approach to sustainable consumer food packaging must consider diet trends and the necessary transformation of food systems.

There is no question that packaging innovations suitable for perishable, nutritious foods are essential for these transformations. In the next and final blog post, we will explore the future of sustainable food packaging.

Jocelyn Boiteau is a TCI alumna and director of nutrition impact and innovation at Food Systems for the Future.

Featured image: Tomatoes are sold in plastic packaging at a grocery store in Hyderabad, India. (Photo by Jocelyn Boiteau/TCI)